Yesterday I was invited to give a talk at the Drexel University Library and in a fit of hubris I decided to attack a problem that many of us in academia face: how to interact with society, engage your students, get your papers read, not become an “empty” entertainer, while avoiding burnout and staying happy… The actual title to the talk was slightly less ambitious but maybe a bit of a downer: “Nobody cites your work: copyright licensing and public engagement”

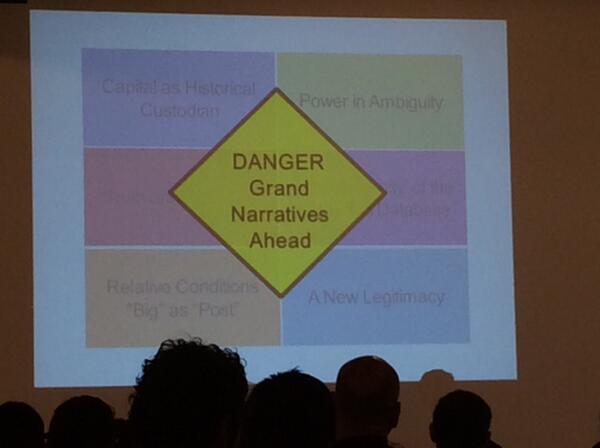

These are questions which have long been close to my heart but it was great to be given the opportunity to be able to share my thoughts about what we should or could be doing about this. The presentation began with me explaining that there will be no easy answer to all the questions I pose but that we as a community of academics must continue to raise awareness in these issues in order not to be overcome with them. So the talk would really present some issues, solutions, and a critique.

The issues I wanted to address were interaction, students, being ignored, and edutainment.

Interaction: The was a response to the recent critique by Nicholas Kristof Academics, We need you! in which he wrote

“If the sine qua non for academic success is peer-reviewed publications, then academics who ‘waste their time’ writing for the masses will be penalized.”

and the article by Joshua Rothman Why is academic writing so academic? in which he wrote

“Academic prose is, ideally, impersonal, written by one disinterested mind for other equally disinterested minds”

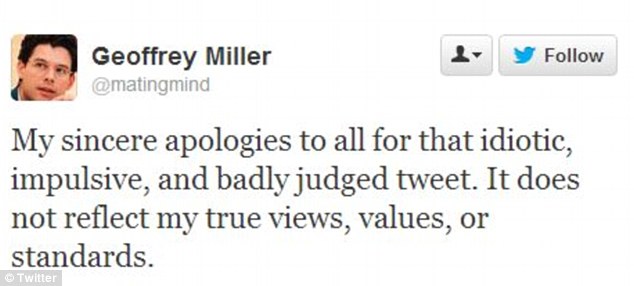

There have been much written about these two articles and suffice to say that there is a perception problem when the hoards of engaged and enthusiastic academics that I know and work with are being portrayed as dated, distant, and disinterested. I’ve written more on this earlier here and the links are rewarding. The difference between perception and reality is what makes this a real problem.

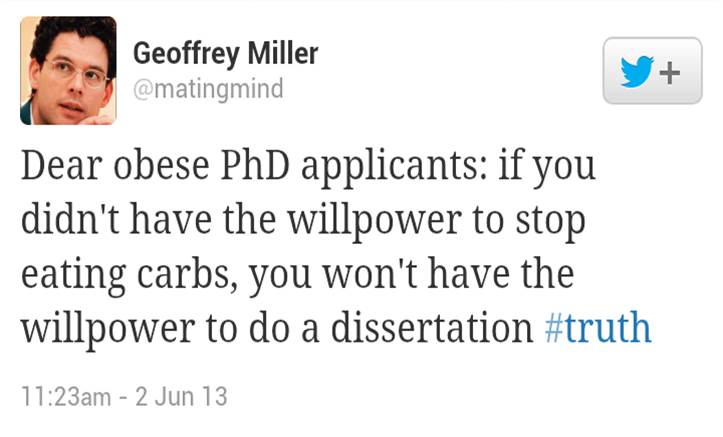

Students: Many of our students are as young as 18 years old. This means that they were 8 years old when Facebook emerged. They have been online, using technology, and being shaped by digital technology for all of their lives. In order to communicate meaningfully to them we must be prepared to both demand that they struggle but simultaneously understand that they are shaped by the environment. A quote by Missy Cummings puts this into perspective (BBC The Why Factor: Boredom):

“We’d be lucky today if they had a 20-30 minute attention span, now its more like 5-10, because if their minds wander they immediately go to another information seeking routine like their cell phones… Like it or not this is the new norm.“

Yes of course we can be upset about this development. But more importantly we must accept this development to be part of the reality of teaching today.

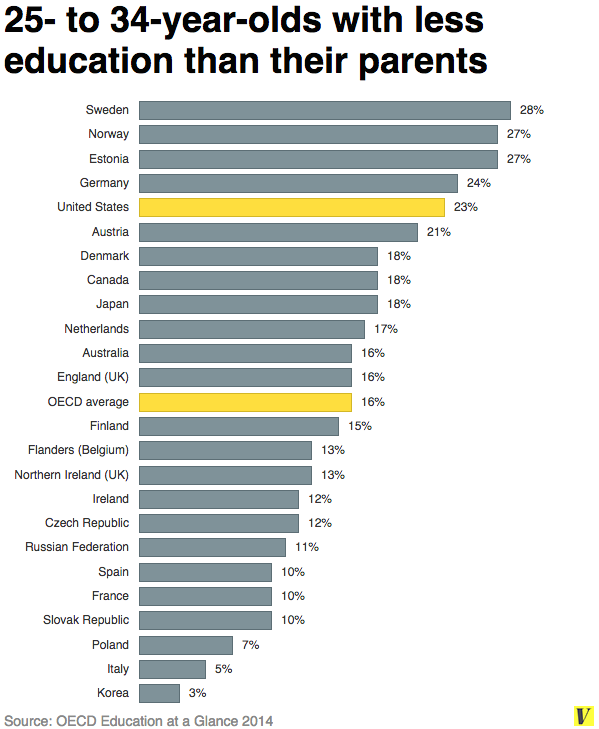

Being ignored:This is the incredibly disheartening realization that lies at the heart of academic publishing. Lokman I Meho The Rise and Rise of Citation Analysis

“It is a sobering fact that some 90% of papers that have been published in academic journals are never cited. Indeed, as many as 50% of papers are never read by anyone other than their authors, referees and journal editors.”

Between the amount of time academics spend on unsuccessful grant applications and creating articles which are unread it is difficult not to throw ones arms up in the air and scream in frustration.

Edutainment: This is the unreasonable expectation that learning should be fun. Of course learning can be fun. But actually learning the basics of something is a challenge and the pride one feels after mastering something comes as a result of the effort it takes. If it’s all fun then maybe it’s not really effort? The problem that education should be fun is partly caused by the snappy lectures presented in short pithy formats like the TED’s. The TED isn’t about basic education. It’s about small ideas with personal experiences and easy to swallow segments. Imagine trying to learn a foreign language, programming or the finer details of procurement law in TED talks! Unfortunately the talks have sometimes been presented as the future of education. For more on TED’s negative effects and sources to its critics see The Cult of TED harms lectures.

Following a presentation of the issues I wanted to address some of the solutions being put forward social media, open access, and licensing. These were presented with the understanding that taken as general one-size-fits-all solutions they are not particularly usable. The reason for presenting this set of “solutions” was also to enable the discussion on the shallow critics which have been particularly vocal in a couple of articles in The Scholarly Kitchen. First there was CC-BY, Copyright, and Stolen Advocacy and then there was Does Creative Commons Make Sense? these articles were critiqued in the comments but they still stand as a voices of criticism. In particular the latter article attempts to argue that CC is unimportant because copyright law exists. Sad statement, a rebuttal could fill several books… oh, wait it they already exist.

As a slight aside, as I couldn’t resist pointing it out, the existence of law does not in itself protect the individual. I told the audience of the situation where Lawerence Lessig (copyright professor and activist and founder of CC) was sued for posting a lecture online. He argued fair use and eventually won his case. But would many professors have the knowledge, tenacity and support to fight in cases such as these?

Following this I presented a quick intro to Creative Commons licensing including a small description into the progression from version 1 to the current version 4 of the licenses. Then I moved on the lecture to the analysis. Does social media and lowering barriers work and if so how and how much?

The material I presented was a mix of cases with the efficiency of open access and open content licensing in making material available to larger groups of people. These systems also have the ability to make material available to groups who would not have access through the channels we as academics take for granted. When I came to the discussion on whether or not open access helps I used this article Open Access increases citation? A brief overview of two reports

Two different methods and two different results. Which one is more accurate? It is hard to determine. Open Access is not a panacea for all problems. It does not automatically increase the level of citations. But, without doubt, it helps when it comes to getting more visibility, which obviously is of a great advantage for the articles and their authors. There are other factors in play which shape the level of citations for specific paper; for example the Impact Factor of journal, promotion efforts of publisher and author himself, the chosen subject and field of research, as well as an extended reference list at the end of a research paper. All these factors may have impact on citations level. But all in all, almost all studies into this subject confirm – direct or indirect – positive impact of Open Access on level of citations.

The result of everything? Lowering barriers helps academics, social media can increase range. All must be used with knowledge and caution in order not to become worthless and we need to be knowledgeable about our realities in order to carry out a well informed discussion. Now, find your comfort level & share your work!

Here are the slides I used: