rights

Public/Private Spaces: Notes on a lecture

The class today was entitled Public/Private Spaces: Pulling things together, and had the idea of summing up the physical city part of the Civic Media course.

But before we could even go forward I needed to add an update to the earlier lectures on racial segregation. The article The Average White American’s Social Network is 1% Black is fascinating and not a little sad because of its implications.

In the meantime, whites may be genuinely naive about what it’s like to be black in America because many of them don’t know any black people. According to the survey, the average white American’s social network is only 1% black. Three-quarters of white Americans haven’t had a meaningful conversation with a single non-white person in the last six months.

The actual beginning of class was a response to the students assignment to present three arguments for and three arguments against the Internet as a Human Right. In order to locate the discussion in the context of human rights I spoke of Athenian democracy and the death of Socrates, and the progression from natural rights to convention based rights. The purpose was both to show some progression in rights development – but also to show that rights are not linear and indeed contain exceptions from those the words imply. The American Declaration of Independence (1776) talks of all men

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

but we know that this was not true. Athenian democracy included “all” people with the exception of slaves, foreigners and women. So we must see rights for what they are without mythologizing their power.

In addition they cannot seen in isolation. For example the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789) came as a result of the French Revolution include many ideas that appear in similar rights documents

- Men are born and remain free and equal in rights.

- Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else.

- Law is the expression of the general will

- No punishment without law

- Presumtion of innocence

- Free opinions, speech & communication

The similarities are unsurprising as they emerge from international discussions on the value of individuals and a new level of thought appearing about where political power should lie.

The discussion then moved to the concept of free speech and the modern day attempts to limit speech by using the concept of civility, and interesting example of this is explained in the article Free speech, ‘civility,’ and how universities are getting them mixed up

When someone in power praises the principle of free speech, it’s wise to be on the lookout for weasel words. The phrase “I favor constructive criticism,” is weaseling. So is, “You can express your views as long as they’re respectful.” In those examples, “constructive” and “respectful” are modifiers concealing that the speaker really doesn’t favor free speech at all.

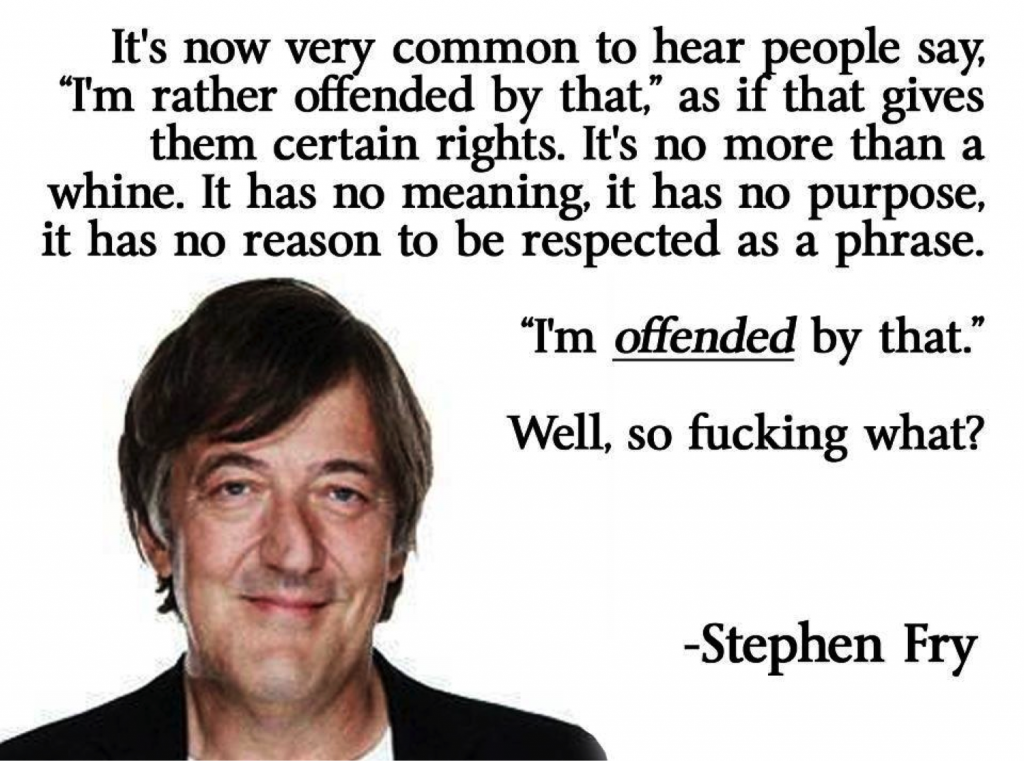

Free speech is there to protect speech we do not like to hear. We do not need protection from the nice things in life. Offending people may be a bi-product of free speech, but a bi-product that we must accept if we are to support free speech. Stephen Fry states it wonderfully:

At this point we returned to the discussion of private/public spaces in the city and how these may be used. We have up until this point covered many of the major points and now it was time to move on to the more vague uses. Using Democracy and Public Space: The Physical Sites of Democratic Performance by John Parkinson we can define public as

At this point we returned to the discussion of private/public spaces in the city and how these may be used. We have up until this point covered many of the major points and now it was time to move on to the more vague uses. Using Democracy and Public Space: The Physical Sites of Democratic Performance by John Parkinson we can define public as

1.Freely accessible places where ‘everything that happens can be observed by anyone’, where strangers are encountered whether one wants to or not, because everyone has free right of entry

2.Places where the spotlight of ‘publicity’ shines, and so might not just be public squares and market places, but political debating chambers where the right of physical access is limited but informational access is not.

3.‘common goods’ like clean air and water, public transport, and so on; as well as more particular concerns like crime or the raising of children that vary in their content over time and space, depending on the current state of a particular society’s value judgments.

4.Things which are owned by the state or the people in and paid for out of collective resources like taxes: government buildings, national parks in most countries, military bases and equipment, and so on.

and we can define private as:

1.Places that are not freely accessible, and have controllers who limit access to or use of that space.

2.Things that primarily concern individuals and not collectives

3.Things and places that are individually owned, including things that are cognitively ‘our own’, like our thoughts, goals, emotions, spirituality, preferences, and so on

In the discussion of Spaces we needed to get into the concept of The Tragedy of the Commons (Hardin 1968) which states that individuals all act out of self-interest and any space that isn’t regulated through private property is lost forever. This ideology has grown to mythological proportions and it was very nice to be able to use Nobel prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom to critique it:

The lack of human element in the economists assumptions are glaring but still the myth persists that common goods are not possible to sustain and that government regulation will fail. All that remains is private property. In order to have a more interesting discussion on common goods I introduced David Bollier

A commons arises whenever a given community decides that it wishes to manage a resource in a collective manner, with a special regard for equitable access, use and sustainability. It is a social form that has long lived in the shadows of our market culture, but which is now on the rise

We will be getting back to his work later in the course.

In closing I wanted to continue the problematizing the public/private discussion – in particular the concepts of private spaces in public and public spaces in private. In order to illustrate this we looked at these photos:

Just a Kiss by Shutterpal CC BY NC SA

A sign of the times: red hair, red headphones by Ed Yourdon cc by nc sa

The outdoor kiss is an intensely private moment and it has at different times and places been regulated in different manners. The use of headphones and dark glasses is also a way in which private space can be enhanced in public. These spaces are all around us and form a kind of privacy in public.

The study of these spaces is known as Proxemics: the study of nonverbal communication which Wikipedia defines as:

Prominent other subcategories include haptics (touch), kinesics (body movement), vocalics (paralanguage), and chronemics (structure of time). Proxemics can be defined as “the interrelated observations and theories of man’s use of space as a specialized elaboration of culture”. Edward T. Hall, the cultural anthropologist who coined the term in 1963, emphasized the impact of proxemic behavior (the use of space) on interpersonal communication. Hall believed that the value in studying proxemics comes from its applicability in evaluating not only the way people interact with others in daily life, but also “the organization of space in [their] houses and buildings, and ultimately the layout of [their] towns.

The discussions we have been having thus far have been about cities and the access and use of cities. How control has come about and who has the ability and power to input and change things in the city. Basically the “correct” and “incorrect” use of the technology. Since we are moving on to the public/private abilities inside our technology I wanted to show that we are more and more creating private bubbles in public via technology (our headphones and screens for example) and also bringing the public domain into our own spaces via, for example, Facebook and social networking.

We ended the class with a discussion on whether Facebook is a public or private space? If it is a private space what does it mean in relation to law enforcement and governmental bodies? If it is a public space when is it too far to stalk people? And finally what is the responsibility of the platform provider in relation to the digital space as public or private space?

here are the slides I used:

Could Facebook be a members only social club?

What is public space? Ok, so it’s important but what is it and how is it defined? The reason I have begun thinking about this again is an attempt to address a question of what government authorities should be allowed to do with publicly available data on social networks such as Facebook.

One of the issues with public space is the way in which we have taken it’s legal status for granted and tend to believe that it will be there when we need it. This is despite the fact that very many of the spaces we see as public are actually private (e.g. shopping malls) and many spaces which were previously public have been privatized.

So why worry about a private public space? Who cares who is responsible for it? The privatization of public space allows for the creation of many local rules which can actually limit our general freedoms. There is, for example, no law against photographing in public. But if the public space is in reality a private space there is nothing stopping the owners from creating a rule against photography. There are unfortunately several examples of this – only last month the company that owns and operates the Glasgow underground prohibited photography.

Another limitation brought about by the privatization of public spaces is the limiting of places where citizens can protest. The occupy London movement did not chose to camp outside St Paul’s for symbolic reasons but because the area land around the church is part of the last remaining public land in the city.

Over the last 20 years, since the corporation quietly began privatising the City, hundreds of public highways, public pathways and rights of way in place for centuries have been closed. The reason why this is so important is that the removal of public rights of way also signals the removal of the right to political protest. (The Guardian)

This is all very interesting but what has it got to do with Facebook?

In Sweden a wide range of authorities from the Tax department to the police have used Facebook as an investigative tool. I don’t mean that they have requested data from Facebook but they have used it by browsing the open profiles and data available on the site. For example the police may go to Facebook to find a photograph, social services may check up if people are working when they are claiming unemployment etc.

What makes this process problematic is that the authorities dipping into the Facebook data stream is not controlled in any manner. If a police officer would like to check the police database for information about me, she must provide good reason to do so. But looking me up on Facebook – in the line of duty – has no such checks.

These actions are commonly legitimized by stating that Facebook is a public space. But is it? Actually it’s a highly regulated private public space. But how should it be viewed? How should authorities be allowed to use the social network data of others? In an article I am writing right now I criticize the view that Facebook is public, and therefore accessible to authorities without limitation. Sure, it’s not a private space, but what about a middle ground – could Facebook be a members only social club? Would this require authorities to respect our privacy online?

The importance of anonymity

Last night some Norwegian friends and I had a long protracted discussion on the “right” or importance of online anonymity.

Since the mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik was active in forums online and was inspired in part by other anonymous racists (such as Fjordman) there has been a question as to whether anonymity online should be curtailed.

Now it’s difficult to argue in light of what the murderer Breivik did. But removing online anonymity would not have prevented his acts. Removing online anonymity after Utöya will only damage the ability of a broad democratic discussion.

At this stage some argue that if you have an opinion you should (as in must – state it openly, not anonymously). The most commonly used cliché is that you have nothing to fear if you have nothing to hide.

The problem is that the people who say: Nothing to fear if you have nothing to hide are safe. They live in reasonable comfort, security and normality. They may truly have nothing to hide. But the importance of the right is not to protect those who have nothing to hide – but to protect those who might be hurt for taking part in a democratic debate.

The right of anonymity – as with most rights – is there to protect those who are at risk. If you are not at risk then you may not see the need for rights.

A simple example is the rights of women. Why did it take so long for women to be given the vote? This basic right to participate in the democracy. Well, in part, those in power were men. These men could not see anything wrong with the system – or see any need for women to have rights.

Or why not the right to free speech? You do not need protection (which the right guarantees) to say nice things, you need the protection to say unpleasant things, to say things that people may not want to hear – but that need to be said.

Pointing out my good points requires no courage or protection – but also pointing out my good points, while making me happy, does not enable me to grow. Pointing out my flaws may make me less happy, and is more courageous (potentially dangerous and requires protection) but it gives me an indication of what needs to be done. It is more important for a society to hear about its flaws than its benefits.

Society needs to help and support those individuals who are about to be courageous. We need to have the arguments, discussions and wacky ideas brought to the surface. Anonymity is not the problem – the problem is when people are afraid of discussion because they may be sanctioned or harmed: socially, economically or psychologically.

Removing civil rights without appearing to be a dictorship

Many of the civil rights that we today claim to be “natural” or “fundamental” have their roots in an ideology of the individual which dates back to the 18th century. The importance of a free press, free speech, democracy and the fundamentals of integrity can be traced back to the enlightenment period which believed that all were created equal and that people – not systems – were valuable and important enough to be in control.

Since then these ideologies have been slowly been implemented into law. Not uniformly nor quickly but still the ongoing process of bringing implemented, real civil rights has been measurable. But lets not get carried away. One thing lacking in our (for example) right to expression has been our ability to express ourselves to a wider audience. Sure we have the right to do so – but do we have the ability to do so?

The fact that not everyone could speak was seen as unfortunate but inevitable and this scarcity created a marketplace of ideas. Well, in reality, it created a marketplace of platforms from which to speak from. If you fit the profile of the platform you may (still if you are lucky) exercise your right to speak to a larger audience.

In this way many of our rights are strongly linked to the platforms which give us the ability to carry out these rights. And what are the Internet, the Web & Web2.0? They are a form of easily accessible platforms. The barriers to entry to these platforms are widely reduced (compared with old or traditional media). With the lowering of barriers to entry millions (?) of people have been exercising rights which have previously only been theoretical.

Unfortunately this does not suit everyone. What we have seen is that with the removal or reduction of technical or economic barriers to entry the law is often being used to create an artificial barrier to reduce or minimize the impact of our rights.

Now the interesting thing is that no politician today would dare to challenge the enlightenment ideal. No politician today can openly say that they want to reduce our fundamental freedoms even if they are tempted to. What happens instead is the interesting removal of rights by creating levels of control in our communications intermediaries. What this means is that instead of telling people that they will reduce their rights governments are applying burdens of surveillance and control on the companies that provide our infrastructure.

And what can we do? Well not much really. Most of our infrastructure use is voluntary. If we want to use the net we are forced to play along with the conditions of the companies that provide the net to us.

A recent example of this process (one of many) reported by Wired is that the Obama administration is urging Congress not to adopt legislation that would impose constitutional safeguards on Americans’ e-mail stored in the cloud.

As the law stands now, the authorities may obtain cloud e-mail without a warrant if it is older than 180 days, thanks to the Electronic Communications Privacy Act adopted in 1986. At that time, e-mail left on a third-party server for six months was considered to be abandoned, and thus enjoyed less privacy protection. However, the law demands warrants for the authorities to seize e-mail from a person’s hard drive.

A coalition of internet service providers and other groups, known as Digital Due Process, has lobbied for an update to the law to treat both cloud- and home-stored e-mail the same, and thus require a probable-cause warrant for access. The Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on that topic Tuesday.

The companies — including Google, AOL and AT&T — maintain that the law should be changed to reflect that consumers increasingly access their e-mail on servers, instead of downloading it to their hard drives, as a matter of course.

But the Obama administration testified that imposing constitutional safeguards on e-mail stored in the cloud would be an unnecessary burden on the government. Probable-cause warrants would only get in the government’s way.

The process is an excellent example of the cynical application of power. On the face of it government still maintains its support for rights, while in reality slashing the practical application of rights at the point of the technology upon which the rights stand.

Limiting the Open Society: notes from a lecture

Today I was presenting on the FSCONS track of the GoOpen conference in Oslo and the topic for my talk was Limiting the Open Society: Regulation by proxy

To set the stage for my talk I began by asking the question why free speech was important. This was closely followed by a secondary question asking whether or not anyone was listening.

The point for beginning with this question was to re-kindle the listeners interest in free speech and also to wake the idea that the concept of free speech maybe is something which belongs in the past a remnant of a lost analog age which should be seen as a quaint time – but not relevant today.

Naturally it was not possible to present a full set of articles on the reasons for why free speech is important during a 20 minute presentation but I could not help picking up three arguments (with a side comment asking whether anyone could imagine a politician saying free speech was unimportant).

The main arguments were

John Stuart Mill’s truth argument presented in On Liberty (1869) from which this quote is central:

“However unwillingly a person who has a strong opinion may admit the possibility that his opinion may be false, he ought to be moved by the consideration that however true it may be, if it is not fully, frequently, and fearlessly discussed, it will be held as a dead dogma, not a living truth”

Basically Mill’s argument can be broken down into four parts:

- The oppressed may represent the truth

- Without criticism we are left with dead dogma

- Opinion without debate meaningless

- Deviant opinions may be unaccepted truth

The second argument I presented was from Lee Bollinger’s The Tolerant Society: Freedom of Speech and Extremist Speech in America (1986)

Bollinger argues that the urge to suppress disagreeable speech is part of a need to suppress all ideas and behavior that threaten social stability. While Mill argues that it is important to support speech because it maybe right Bollinger argues that habits of tolerance in all its forms (including speech) are important to combat paternalism.

“…the free speech principle involves a special act of carving out one area of social interaction for extraordinary self-restraint, the purpose of which is to develop and demonstrate a social capacity to control feelings evoked by a host of social encounters.”

The final argument I presented was one of positive law – free speech is important because the law says it is important. The high point of this argument can be seen as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which created an international understanding of the importance of rights (including speech).

After this introduction I presented the concepts in an historical background. Again I needed to be brief so I could not really go into detail. I jumped straight into the period 300 years ago when the discussion on the rights of man in Europe was at a high point. The fear of censorship in advance (imprimatur) or punishment after the fact was of great interest. The results of these discussions were documents like The Rights of Man and the Citizen presented after the French revolution, the United States Declaration of Independence and the Swedish Freedom of the Press Act of 1766.

The problems with these documents and the regulatory acts which followed where that they presented potential rights but did nothing to ensure access to communications media. In fact the communications media became ever more centralized and access was granted to a more and more limited group of (similarly minded) people. The negative aspect of this situation were (1) centralized media can easily be controlled and (2) allowing small group access means that the individual members have to conform to remain in the in-group.

To re-enforce the concept of in-group and out-group I showed an image of the speaker’s corner in London where any individual may speak without being harassed its not a legal right even if it seems to be an established practice. Speaker’s corner is sometimes seen as an example of openness but in reality it is proof of the failure of our ability to speak openly anywhere.

Then we moved quickly along to the Internet as an example of where a technology was developed that made personal mass communication available to a wider audience.

The exciting thing about the Internet is that it carries within it freedom as a side effect of its creation. This freedom was developed by common agreement (of a homogeneous group) into the open end-to-end, packet switching “liberal” ideology that we experienced in the early days of technology.

Naturally the problem with any idea that is developed under a consensus is that any use, concept, idea or speech which falls outside the consensus is easily suppressed and lost. But more on this later.

In the early days we were overly optimistic and believed texts such as John Perry Barlow’s A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace:

Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather.

But naturally this was not going to last since the freedom we relied on was in reality a bi-product of corporate activity.

Our reliance on technology is a reliance on services created and provided mainly by corporate actors. And corporate actors have different priorities. It’s not about individual goodwill but it is about profit. Milton Friedman wrote in Capitalism and Freedom (1962)

There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits…

It is not evil for companies to be all about profit but if there ever is a clash between individual freedom and profit then the corporation has an obligation to focus on profit at the cost of freedom.

At this stage at the lecture I shifted on to the problem of censorship. First I addressed the issue of self-censorship and used a quote by George Orwell on the topic.

Circus dogs jump when the trainer cracks his whip, but the really well-trained dog is the one that turns his somersault when there is no whip.

It is very difficult for us to know that we are censoring ourselves.

The next problem is the fact that even if we have something to say this does not mean that there is anyone who will (or can) listen. Basically we are lost in crowds.

These first two hindrances to communication are inevitable but they also create a bias against speech and the spread of ideas. From this point I began to address issues that can be (and should be) addressed.

The first issue was affordances. I showed the image of by Yumiko Hayakawa of the ‘Anti-Homeless’ park bench. And as I always do I asked the audience to spot the ethical problem in the image. The problem is that the bench discriminates among users by allowing only certain types of use. People with weak legs (old people?) struggle to use this bench, no people will loiter on this bench, and naturally no homeless people can sleep on this bench.

image from Yumiko Hayakawa essay Public Benches Turn ‘Anti-Homeless’ (also recommend Design with Intent)

Without engaging in a wider discussion the park authority can implement regulation without rules. No law expelling homeless people is necessary and therefore no legal review is ever carried out.

On the topic of affordances I brought up the German engineer problem. Here is the story behind the creation of SMS messaging (LA Times)

Alone in a room in his home in Bonn, Germany, Friedhelm Hillebrand sat at his typewriter, tapping out random sentences and questions on a sheet of paper.

As he went along, Hillebrand counted the number of letters, numbers, punctuation marks and spaces on the page. Each blurb ran on for a line or two and nearly always clocked in under 160 characters.

That became Hillebrand’s magic number — and set the standard for one of today’s most popular forms of digital communication: text messaging.

“This is perfectly sufficient,” he recalled thinking during that epiphany of 1985, when he was 45 years old. “Perfectly sufficient.”

Since then Twitter was developed from SMS and therefore we see how a engineer speaking German is today controlling the way in which we communicate today.

Another form of censorship is the whole problem of the chilling effect of law when it’s law is applied in situations where it has the effect of limiting speech – even if the purpose of the law was something completely different.

As a final form of censorship I spoke about the negative effects of End-User License Agreements (EULA). Many of the platforms upon which we depend for our communication have demanded of us that we agree to terms of use which we may not understand or which may have changed dramatically since we last read them. The result is that users are stuck in a perpetually weak situation.

So what’s really going on? Why doesn’t the state act or react to the erosion of our rights. These rights which are apparently so fundamental and important.

Well in part its lack of knowledge. Many states do not know the problems we are facing. The second part is that these are contractual agreements and the state is concerned about intervening in agreements (between consenting parties) and finally – and more ominously – the state benefits from the system.

States are able to stand tall and use words like rights, democracy, speech without limiting or censoring. They don’t have to. What the state does is they require acts (like data retention or surveillance) carried out by our service providers. If the state needs anything it can then collect it from the providers. The good news is that the state can claim to have clean hands. This is regulation by proxy.

So what can be done? Here I presented three strategies:

First, keep focused; remember what free speech is for. A second quote from George Orwell, this time from his preface of Animal Farm:

If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.

Second a demand that the state should end regulation by proxy and return to its own purpose. And the protection of citizen’s rights should include limiting the rights of actors. Speech on any medium should be protected – not only from the acts of the state.

Thirdly. The third was not really a new suggestion but more of an alternative. If the state cannot protect our speech then it should declare free speech as a thing of the past a remnant of a bygone analog age. This will not help much – but at least it will stop the hypocrisy.

Iceland tomorrow!

Tomorrow I am off to Iceland! This is really cool even though I wish I was staying there for a longer period of time. But it’s cool enough. I fly up tomorrow, have meetings on Tuesday and fly home early on Wednesday. The meetings should be very interesting since I am there to participate in discussions on Tryggvi Björgvinsson‘s thesis, there will be meetings with the Icelandic Society for Digital Freedom. Also I should be able to squeeze in some sightseeing between airports.

Why would sub-democratic leaders blog?

Listening to the radio this morning and heard that Karim Massimov, the Prime Minster of Kazakhstan started his private, yet official blog on 9th January and apparently has been so happy with the result that he has ordered his minsters to start personal blogs.

A politician starting a blog is hardly worth mentioning and starting in 2009 seems even to be a late starter but this one is a bit interesting.

According to the American State Department Country Report on Kazakhstan

The Government’s human rights record remained poor, and it continued to commit numerous abuses. The Government severely limited citizens’ right to change their government and democratic institutions remained weak. On some occasions, members of the security forces, including police, tortured, beat, and otherwise mistreated detainees; some officials were punished for these abuses. Prison conditions remained harsh; however, the Government took an active role in efforts to improve prison conditions and the treatment of prisoners. The Government continued to use arbitrary arrest and detention and to selectively prosecute political opponents; prolonged detention was a problem. Amendments to several laws governing the authority of procurators further eroded judicial independence. The Government infringed on citizens’ privacy rights.

Reporters sans frontières begin their 2008 report on Kazakhstan:

As well as the usual problems journalists get when they expose corruption or criticise President Nazarbayev, the media was the victim of power struggles inside the regime. Three opposition journalists died in suspicious circumstances and coverage of the August 2007 parliamentary elections was biased.

So the idea that the Prime Minister of Kazakhstan starting a blog and praising the way in which it allows citizens to communicate more directly with government is surprising to say the least. Either the whole thing is a propaganda attempt gone wrong or a total misunderstanding of the power of online communication.

Or maybe those in power just don’t get how bad they are?

Protecting Digital Rights

Internet service providers are hardly known for their efforts to protect the rights of their clients. This is hardly surprising considering they low amount of money they make per client compared to the legal costs which would be entailed in attempting to defend a client. For example: A cheap web hosting service costs less per year than a lawyer costs per hour. It’s not too difficult to work it out.

At the same time the ISPs are our lifeline and basis of our ability to participate in a digital society so this lack of help is a serious flaw. So it was nice to see that the Council of Europe have published Human rights guidelines for Internet service providers

Developed by the Council of Europe in close co-operation with the European Internet Services Providers Association (EuroISPA), these guidelines provide human rights benchmarks for internet service providers (ISPs). While underlining the important role played by ISPs in delivering key services for the Internet user, such as access, e-mail or content services, they stress the importance of users’ safety and their right to privacy and freedom of expression and, in this connection, the importance for the providers to be aware of the human rights impact that their activities can have.

in addition to this document the Council of Europe have also published Human rights guidelines for online games providers

Developed by the Council of Europe in close co-operation with the Interactive Software Federation of Europe (ISFE), these guidelines provide human rights benchmarks for online games providers and developers. While underlining the primary value of games as tools for expression and communication, they stress the importance of gamers safety and their right to privacy and freedom of expression and, in this connection, the importance for the games industry to be aware of the human rights impact that games can have.

Documents such as these are the early steps at ensuring the protection of individuals online rights and as such should be applauded even if it is kind of worrying that we still see a need to attempt to define rights in online environments as something fundamentally different from human rights in the offline world.

Remove wood from your eyes

From the cartoonist Matt Davis comes this excellent political satire on Bush’s attempt to criticize China’s human rights (BBC video here), his “…deep concerns religious freedom and human rights…”

and that was even before Georgia…