Summer 2020 Online

These are the notes that usually form the basis for my live lectures. I am putting them here as a support for the sudden and unplanned move to online teaching due to Covid-19. If I have missed or misrepresented a source please reach out to me.

“Everyone is guilty of something or has something to conceal. All one has to do is look hard enough to find what it is.” Cancer Ward by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

What is Privacy?

In his book Privacy & Freedom (1967) Alan Westin states that “Privacy is the claim of individuals, groups or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others.” (p. 7). In his book he argues that there are four basic states of privacy:

- Solitude – the desire to be separate from the group

- Intimacy – the ability to have a close relationship with another (or others)

- Anonymity – the ability to be visible without identification or surveillance

- Reserve – the most subtle state: the “creation of a psychological barrier against unwanted intrusion

Think about the meanings of solitude, intimacy, anonymity, and reserve. How do you think they relate to your ideas of privacy.

Daniel Solove‘s book Understanding Privacy (2008), attempts to understand the complex and contradictory modern views and approaches to privacy. He points out that “privacy concerns and protections do not exist for their own sake; they exist because they have been provoked by particular problems”. He begins by dividing privacy into six (often overlapping) types of privacy:

- the right to be let alone – Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis’ famous formulation of the right to privacy;

- limited access to the self – the ability to shield oneself from unwanted access by others;

- secrecy – the concealment of certain matters from others;

- control over personal information – the ability to exercise control over information about oneself;

- personhood – the protection of one’s personality, individuality, and dignity; and

- intimacy – control over, or limited access to, one’s intimate relationships or aspects of life. (13)

Does this list increase/improve on Westin’s ideas? What has changed since 2008? What, if anything, is missing?

Is it universal?

One of the many issues that occur when discussing privacy is the question of universality, i.e. can we define something as vague as privacy, and would such a definition be applicable everywhere?

Consider this quote from Jared Diamond‘s book The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? (2012)

“Because hunter-gatherer children sleep with their parents, either in the same bed or in the same hut, there is no privacy. Children see their parents having sex. In the Trobriand Islands, Malinowski was told that parents took no special precautions to prevent their children from watching them having sex: they just scolded the child and told it to cover its head with a mat” (page 202)

Can you think of examples where concepts of privacy differ between time, space, or culture?

Is Privacy good?

The next question we could ponder over is whether privacy is always a benefit or good?

In the summer of 1963, anthropologist Jean Briggs journeyed to the Canadian Northwest Territories (now Nunavut) to begin a seventeen-month field study of the Utku, a small group of Inuit First Nations people who live at the mouth of the Back River, northwest of Hudson Bay.

She lived with a family as their “adopted” daughter—sharing their iglu during the winter and pitching her tent next to theirs in the summer. She reflects on how her family ostracized her for daring to to explore the wilderness alone for a day.

“And it dawned on me how forlorn I would be in that wilderness if they forsook me. Far, far better to suffer loss of privacy.” (Never in Anger: Portrait of an Eskimo Family, 1970, page 28).

In what other situations may privacy be a problem/issue/negative?

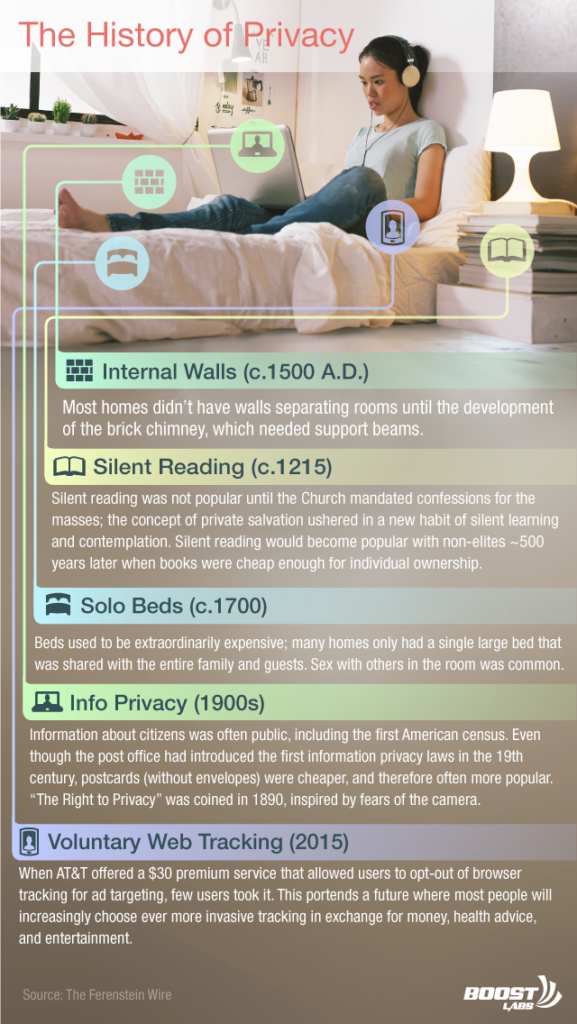

An odd history of privacy

For another eclectic history of privacy check out Greg Ferenstein’s The Birth And Death Of Privacy: 3,000 Years of History Told Through 46 Images (2015). The 5 volume History of Private Life is an amazing resource.

The 1890s discussion

While privacy can be traced back in history, the end of the 1800s saw a rise in the discussion of privacy. This was brought about by a range of social and technical reasons.

The journalist Edwin Lawrence Godkin (1831 – 1902) called privacy “…a distinctly modern product, one of the luxuries of civilization“. (Scribners Magazine, 1890).

The focus on privacy may also be attributed to the growing technologies that enabled novel forms of invasion into privacy. For example the hand held camera and the rise of amateur photography.

By far the most significant event in the history of amateur photography was the introduction of the Kodak #1 camera in 1888. Invented and marketed by George Eastman (1854–1932), a former bank clerk from Rochester, New York, the Kodak was a simple box camera that came loaded with a 100-exposure roll of film. When the roll was finished, the entire machine was sent back to the factory in Rochester, where it was reloaded and returned to the customer while the first roll was being processed. Although the Kodak was made possible by technical advances in the development of roll film and small, fixed-focus cameras, Eastman’s real genius lay in his marketing strategy. By simplifying the apparatus and even processing the film for the consumer, he made photography accessible to millions of casual amateurs with no particular professional training, technical expertise, or aesthetic credentials. To underscore the ease of the Kodak system, Eastman launched an advertising campaign featuring women and children operating the camera, and coined the memorable slogan: “You press the button, we do the rest.”

…

Most snapshots produced between the 1890s and the 1950s were destined for placement in the family album, itself an important form of vernacular expression. The compilers of family albums often arranged the photographs in narrative sequences, providing factual captions along with witty commentary; some albums contain artfully elaborate collages of cut-and-pasted photographs and text, often combining personal snapshots with commercial images clipped from magazines.

Mia Fineman

Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

“amateur photography has the reputation of possessing in its various forms all those seductive charms in the enjoyment of which the weary, earthbound mortal is released from durance vile and translated, for the time being, into some seventh heaven of bliss. Opium, hasheesh, even the fascinations of Monte Carlo are supposed to pall before its many attractions.” New York Tribune 3 July 1892

These luxuries were unevenly distributed , and through this privacy becomes associated with the wealthy, or the bourgeoisie – and as such it becomes aspirational and a class marker.

“The ground floor of every building contains a host of tiny rooms that open directly onto the street and each of these tiny rooms contains a family…they drag tables and chairs out into the street or leave them on the threshold, half outside, half inside…outside is organically linked to inside…yesterday i saw a mother and a father dining outdoors, while their baby slept in a crib next to the parents’ bed and an older daughter did her homework at another table by the light of a kerosene lantern…if a woman falls ill and stays in bed all day, it’s open knowledge and everyone can see her.” J. P. Sartre Lettres au Castor et a quelques autres, Tome 1: 1926-1939 (1983, page 79)

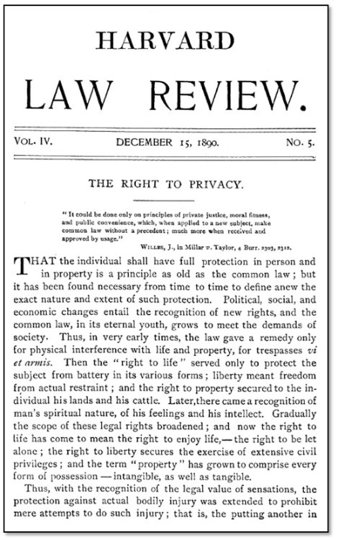

For the privacy scholar (in particular the legal privacy scholar) the year 1890 marks the publishing of the seminal Right to Privacy article by Warren and Brandeis.

The article is concerned about the ways in which society had become increasingly fast paced, and that the level of information intensity may require the recognition of the role of privacy in society.

This could be written about social media or smartphones…

The intensity and complexity of life, attendant upon advancing civilization, have rendered necessary some retreat from the world, and man, under the refining influence of culture, has become more sensitive to publicity, so that solitude and privacy have become more essential to the individual; but modern enterprise and invention have, through invasions upon his privacy, subjected him to mental pain and distress, far greater than could be inflicted by mere bodily injury.

“Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ” what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.”

And Warren & Brandeis faced criticism in their time. The article was well received. For example an article in the 1891 Atlantic Monthly wrote (from Glancy The Invention of the Right to Privacy Arizona Law Review 1979):

…a learned and interesting article in a recent number of the Harvard Law Review, entitled The Right to Privacy. It seems that the great doctrine of Development rules not only in biology and theology, but in the law as well; so that whenever, in the long process of civilization, man generates a capacity for being made miserable by his fellows in some new way, the law, after a decent interval, steps in to protect him.

But an interesting social critique comes from Godkin writing about the Right to Privacy article in The Nation in 1890

The second reason is, that there would be no effective public support or countenance for such proceedings. There is nothing democratic societies dislike so much to-day as anything which looks like what is called “exclusiveness,” and all regard for or precautions about privacy are apt to be considered signs of exclusiveness. A man going into court, therefore, in defence of his privacy, would very rarely be an object of sympathy on the part either of a jury or the public.

He also wrote about how their ideas were interesting but maybe belonged to a certain class of individual… (from Glancy The Invention of the Right to Privacy Arizona Law Review 1979)

” ‘privacy’ has a different meaning to different classes or categories of persons, it is, for instance, one thing to a man who has always lived in his own house, and another to a man who has always lived in a boardinghouse.”

Privacy and its connection to power

“privacy issues . . . might be better described and analyzed as issues of power… The problem with the concept of ‘privacy,’ however defined, is that whatever work it does, its problematic overuse can obscure certain issues of power and consequential harm… those who have power have the luxury of defining what is and what is not private.”

Rosa Ehrenreich, “Privacy and Power,” Georgetown Law Journal 89

(2001–2002), 2047.

As Ehrenreich points out, generally “those who have power have the luxury of defining what is and what is not private.” Therefore The denial of privacy, even in civilized societies, becomes a “mechanism of social control.” Ehrenreich

On Panopticons and Power

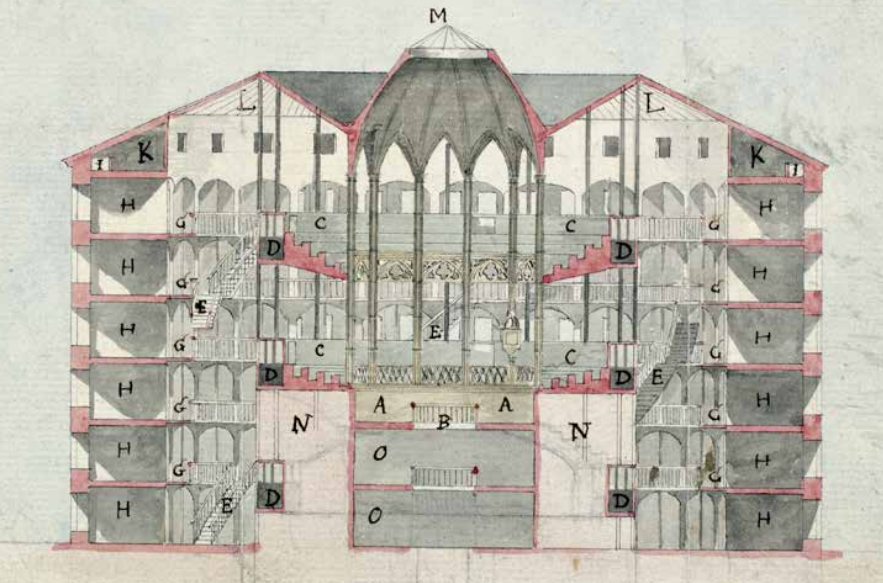

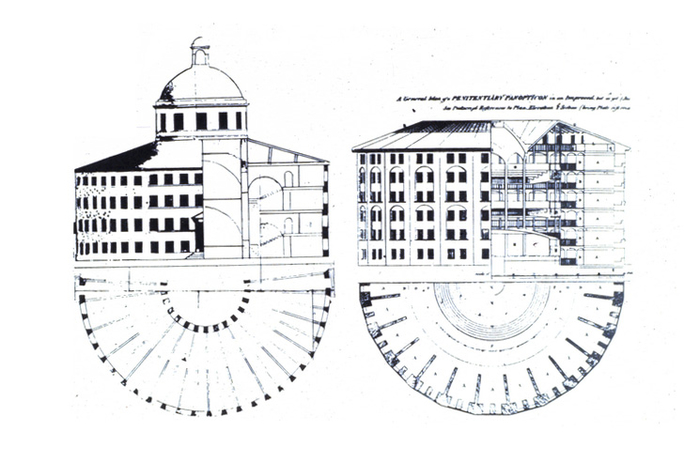

The Panopticon is a type of prison building envisaged by English philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the late eighteenth century. Bentham commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley. The 1843 plans for the panopticon prison were described by Bentham as a “new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in quantity hitherto without example”. Bentham reasoned that if the prisoners of the panopticon prison could be seen but never knew when they were watched, the prisoners would need to follow the rules. Bentham also thought that Reveley’s prison design could be used for factories, asylums, hospitals, and schools.

The concept of the design is to allow an observer to observe (-opticon) all (pan-) prisoners without the prisoners being able to tell if they are being observed or not, thus conveying a “sentiment of an invisible omniscience.” Bentham described in a letter the Panopticon prison as “a mill for grinding rogues honest”

The advantage of this prison was its focus on the labor saving aspect. The guard was in the central tower and could potentially observe all the inmates, but since there were blinds on the tower the inmates could never be certain if they were being observed and thus they obeyed for fear of being seen disobeying (and being further punished).

The prison is interesting and much can be said about it. At the time prisons were not about rehabilitation but about separating the “bad” people from society. The social view at the time was more that badness or goodness was a trait – less than a result of a social setting or class. England, for example deported criminals to the Americas (until the revolution) and then to Australia.

In this light, Bentham’s prison is a reform of the current way of thinking and forms a part of the penitentiary system – with its focus on penance and reform.

Foucault

In his work Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) the philosopher Michel Foucault interprets Bentham’s prison design. He argued that the disciplinary society had emerged in the 18th century and that discipline are techniques for assuring the ordering of human complexities, with the ultimate aim of docility and utility in the system.

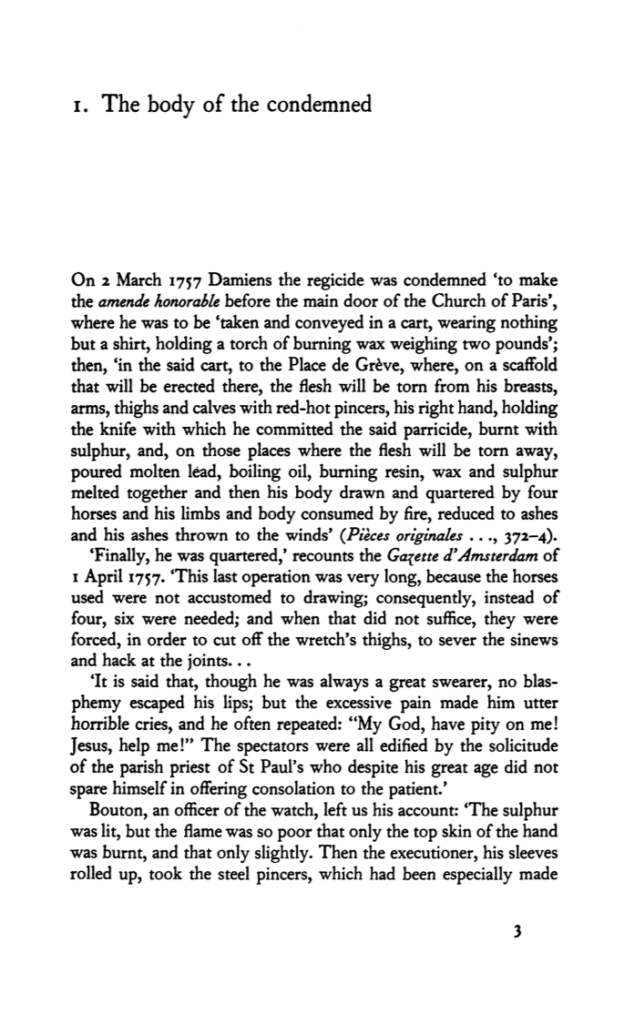

Foucault’s book begins with public execution of Robert-François Damiens who was charged with attempting to assassinate King Louis XV in 1757. Damiens was the last person to be executed in France by drawing and quartering, the traditional form of death penalty reserved for regicides.

Foucault argues that: Power was exercised mainly as a means of deduction, a subtraction mechanism, a right to appropriate a portion of the wealth, a tax of products, goods and services, labor and blood, levied on subjects… a right of seizure… it culminated in the privilege to seize hold of life in order to suppress it. (History of Sexuality v1 page 136).

This is when the power of the state (in this case the monarch) has the ability to decide over life and death. But in the growth of a neoliberal society this power is suppressed and performed through different means. In the latter society there is an increased need for power to be exercised through surveillance.

For him the model can serve as a metaphor for society. “But the Panopticon … is the diagram of a mechanism of power reduced to its ideal form… it is in fact a figure of political technology that may and must be detached from any specific use.” (page 205).

Where Bentham saw the design as a cost efficient (and possibly more humanitarian than deportation) prison, where the inmates internalize their own supervision because they are unaware if they are being observed at any time. Foucault realized that the inmates were internalizing their own surveillance – they became their own guards. But more importantly, for Foucault, this was not about a prison but (as a metaphor) it was the entirety of society.

“Just a gaze, an inspecting gaze which each individual under its weight will end by exteriorizing to the point that he is his own overseer, each individual this exercising this surveillance over and against himself” (Foucault 1980:155)

Indeed we obey not because we can see that we are under surveillance, we obey because of the fear of being under surveillance. This model also scales up nicely and argues that not only are the inmates (all of us) behaving because of fear of being seen, but so are the guards and the prison director. The entire society is behaving because we form part of the panoptic society.

The Panopticon may even provide an apparatus for supervising its own mechanisms. In this central tower, the director may spy on all the employees that he has under his orders: nurses, doctors, foremen, teachers, warders; he will be able to judge them continuously, alter their behaviour, impose upon them the methods he thinks best; and it will even be possible to observe the director himself … enclosed as he is in the middle of this architectural mechanism, is not the director’s own fate entirely bound up with it?

For Foucault the panopticon was

1. Pervasive Power

2. Obscure Power

3. Direct Violence made structural

4. Structural Violence made profitable

What distinguishes Foucault’s and Bentham’s definition of the panopticon is perspective. Bentham is all about “seeing without being seen” but to Foucault the panopticon could not be reduced or framed by a unidirectional gaze from the centre, tower or singular managerial gaze.

“Hence the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power. So to arrange things that the surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action; that the perfection of power should tend to render its actual exercise unnecessary; that this architectural apparatus should be a machine for creating and sustaining a power relation independent of the person who exercises it. In short, that the inmates should be caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers.”

(Foucualt 1977:201)