procrastination

The abundance of books is distraction

Another package arrives and my first thought is the joy of packages. It’s an conditioned response from decades of birthdays and Christmases. Despite knowing what’s inside there is an element of anticipation when I unwrap yet another book that I could not help ordering. Yupp, another book. The joy of holding the book is only marred by the sinking feeling that I should be writing faster, better and to be blunt about it, more. Just more.

There is a sadness in living in a time when there are enormous amounts of books. Most of the books I buy are second hand copies where the postage costs more than the content. Today the gorgeous On Paper: The Everything of it’s two-thousand-year history by a self-confessed bibliophiliac by the prolific Nicholas Basbanes. Thankfully, in this case, the book cost more than the postage.

Read Books by Wrote. CC BY.

But then I leaf through the book, marveling at all the letter, lines, paragraphs, chapters… The weight in my hand and the need to read it. Now. Read. Now. But, there is a pile of necessary books. All relevant to the project and this is just one of many. Place the book in the already precariously balanced pile and sigh while I think that the abundance of books is distraction.

The only thing that calms me is the thought that these words are neither original nor my own. Seneca wrote that the abundance of books is distraction (distringit librorum multitudo). Getting lost in so many books is unhelpful. Anne Bair quotes his explanation to what he means (in another great book: Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age)

You should always read the standard authors; and when you crave change, fall back upon those whom you read before.

And yet, here I am with another great looking book on my desk. It demands my attention and offers me the chance to procrastinate. Reading is not laziness but research, its not procrastination, it’s preparation. And yet the more I read the less text gets produced.

So I do neither: I blog my dilemma.

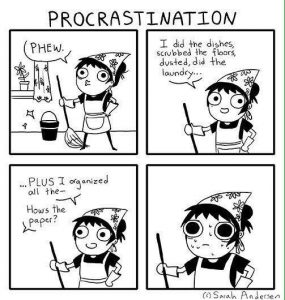

Procrastination is everything

Everything is procrastination…

Procrastination will probably never become a popular competitive sport, but if it ever did I would put most of my money on the PhD students of the world. While it is really difficult to measure procrastination the joy of working on a long-term, individually driven project creates both an extreme familiarity with the concept and the personal hell it entails.

Most people have a vague understanding of their, and others, procrastination abilities. But in a recent conversation in the coffee room I discovered a shocking lack of deeper understanding of the term. Further study is definitely required.

From my own sporadic research I have come to recognize four forms of procrastination: passive, active, positive and entropic. But first lets get some of the theory and definition straight. This is of course easily done by ripping it off Wikipedia:

…procrastination refers to the act of replacing high-priority actions with tasks of lower priority, or doing something from which one derives enjoyment, and thus putting off important tasks to a later time. In accordance with Freud, the Pleasure principle (psychology) may be responsible for procrastination; humans do not prefer negative emotions and handing off a stressful task until a further date is enjoyable. The concept that humans work best under pressure provides additional enjoyment and motivation to postponing a task.

As any good procrastinator will know there is nothing more useful than a minor diagram, preferably using a simple grid which has limited explanatory value but is a major procrastinatory tool in of itself.

Figure 1. Forms of procrastination organized by benefit and control

Figure 1. Forms of procrastination organized by benefit and control

Figure 1 attempts to map out the four major forms of procrastination according to the benefits they bring and the amount of control the individual has over the need to conduct the activity.

Positive procrastination is doing tasks which will actually be beneficial to the main project but doing them in the wrong order. Emptying a mailbox in order to gain time and peace of mind is an excellent example. The individual has a great deal of autonomy in deciding this task and it will, in the long run, be beneficial. However, this benefit will not appear unless the actual task is completed. Therefore the actual benefit of the task is only a potential benefit and conditional to actually not procrastinating.

Active procrastination entails finding something else to do instead of doing the task in hand. This can be everything from laundry, exercising, to re-arranging books. The individual has a great deal of choice in carrying out the task – even if it is commonly defined as necessary in order to do prior to carry out real work. This has actually no benefit at all to the task at hand.

Passive procrastination is doing stuff that the individual has previously agreed to. This is when you look at your calender and realize that the day is full. Therefore the individual maintains the illusion that actual work could be done were it not for the necessity of the meetings previously booked in the calender. Examples of passive procrastination are teaching, administrative meetings or conferences. In passive procrastination the illusion of real progress is masked and, in many cases, the procrastinator is given the opportunity of not defining the tasks as procrastination. These tasks are usually important and beneficial but the level of control is low as we are forced to participate in teaching and administration with a low connection to the job we are procrastinating from.

Entropic procrastination is probably the most harmful form. The body experiences a physical barrier to commencing work and becomes an inert mass. Examples of this? Surfing pointless websites & watching most forms of daytime television.

The problem with the study of procrastination is that the different forms are very difficult to identify objectively and are defined by the lies we tell ourselves.

The lure of procrastination

Phd Comics from the amazing mind and pen of Jorge Cham

Positive Procrastination

While procrastination is often seen as a negative act it does have a positive side. Of course if the procastination we enjoy turns out to be positive and leads to a result – is this really procrastination at all? Hmm an academic Zen koan… but I digress and possibly procrastinate.

Since returning to Göteborg from my Open Access project in Lund there has appeared a small window of opportunity to begin doing something more substantial and long term. So based upon this premise I happily ignore a bunch of more pressing, but smaller, tasks in order to create a meaningful long term project.

Thus far I have located and area, a vague plan of action, a whole bunch of related work and now I am formulating a thesis to be presented, argued and defended. So with the risk of jinxing the project by talking about it at this early stage my idea is to write a book (not very original since I am an academic) on the connection between copyright, culture and innovation.

There! It’s out now. So all I need to do now is to fine tune the thesis and begin purposely bashing the keyboard. Who said that procrastination is all bad?

Post FSCONS procrastination

Now that the weekend FSCONS conference is over and I am sitting in front of the screen again I have that all to familiar feeling of emptiness. I know there is work to be done. I know which work needs to be done, it’s just that I really do not feel like doing it.

This emotional drain occurs most often after handing in a major work or after (as this weekend) a major conference (especially if you are on the arranging team). It’s as if the mind needs to take a break and actively works against serious work.

Bodil Jonsson wrote in her wonderful little book Ten thoughts about time about the concept of “ställtid”. I read her book in the original Swedish so I may translate some words differently. Basically the concept of ställtid is the time you need to arrange stuff around you before you can actually begin doing something. This is particularly important when moving from one task to the next since we often forget to factor such time into the equation.

This arranging time varies in length. Easy and enjoyable tasks require little or no time while complex or dreary tasks require a lot more time before they can be carried out. In some cases these tasks cannot be carried out until the absolutely final moment.

So the fact that we know that we must do something is not enough. Even facing a punishment, fine or dissaproving look is not enough to actually make us do what we must. All this is due to the need of the mind to come to terms with the old tasks and begin preparing for the new tasks.

Most probably this eminent theory of procrastination was written during a period of time when the author was avoiding doing something she really was supposed to be doing. It does not really help me in my situation but it is always nice to know that I am not alone.