This is the resource page for the Fall 2022 Digital Cultures course. Make sure to read the syllabus and please note the version number, it is a living document that will be updated. This course is an exploration into the idea of digitally created and sustained cultures and therefore we need to know a bit about the technology and have a basic understanding of culture in order to be able to understand what a digital culture is – if there even is such a thing.

For a quick basic understanding of (some of) the technologies involved I recommend How the Internet Works: A guide for policy-makers by McNamee et al from European Digital Rights. It does not cover enough but it’s a great start.

Outline

The course follows the following outline. Each module has a module question which will guide the overall discussion of the module but we should be free to explore variations and different directions to the module.

Module 1 Introduction: What is this course about & What the professor expects.

Module 2 What is Culture? The question is in the title.

Module 3 Origins of Digital Culture: What are the differences between the ideas of the future and the present we have?

Module 4 Performing Identities: How is mediated identity formed by the technology?

Module 5 Influencer Culture: What kind of labor is an influencer doing?

Module 6 Digital Fitness Culture: Is fitness technology healthy?

Module 7 Hacker, Maker & Consumer Culture: What is digital consumption?

Module 8 Participatory Culture and Subversive Sharing: Who controls our stories and knowledge?

Module 9 Digital Public Sphere: Does truth matter in democracy?

Module 10 Activist Culture: Why tools matter for the activist?

Module 11 Neo-Luddite Culture: How to maintain control in a technological world?

Module 12 Memory & Forgetting in Obsolescence Culture: Does it matter if digital tools effect our memory?

Module 13 Play Culture: Is it harmful if work becomes play? And play becomes work?

Module 2: What is Culture?

This is a huge question that people have spent their entire careers attempting to answer. So obviously we are going to have to take a quick and dirty look at what it is in order to understand the basics. Once we get the gist of what a culture is and what it does then we can start applying it to the study of digital cultures. Here we go…

These videos from Crash Course Sociology will give you a basic understanding of what culture is and does and should be watched as an extension of the readings. The reading for Module 1 are Schein’s The Three Levels of Culture and Bollmer What Are Digital Cultures? from Theorizing Digital Cultures. For a deeper dive check out Understanding culture from Introduction to Human Geography by R. Adam Dastrup and The Elements of Culture from Introduction to Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by University of Minnesota.

Culture is everything. Not just the high and low culture but every way in which we behave. How close do you stand next to people you don’t know at a bus stop? The answer is (could be) cultural norms.

As a comparison here is are people waiting for the bus in Hong Kong.

Waiting game by Terry Chapman CC BY NC ND

This video from crash course sociology on symbols, values & norms #10 explains and exemplifies the cultural norms that shape our behaviours.

But WHOSE culture is it? Which rules apply? Whats the difference between one person’s behavior and a group culture? When does the culture become… culture? Crash course sociology #11 discusses this and explains the concepts of low and high culture, subcultures, judging other cultures (the issues of ethnocentrism, eurocentrism) and much more…

Which social groups do you belong to? What makes you belong to a group? What does it mean when you belong to a group? Who decides what the group likes/dislikes or does and doesn’t do? This video explores social groups, leadership styles, and our desire to conform to the groups choices.

Vicky Osterweil has written a great essay on subcultures What Was the Nerd? The myth of the bullied white outcast loner is helping fuel a fascist resurgence.

Ok, so now that you get everything about culture – why do we need to study it? Why is it important to identify and understand culture? This video of Julien Bourrelle is a great example of what culture can do…

A large part of the culture discussion in the media has been about appropriation (and about culture wars – more about this later). So what is appropriation?

Cool. But how do we apply all this culture stuff to technology? Check out Mike Rugnetta pondering whether the internet has dialects.

Module 3: Origins of Digital Culture

Module question: What are the differences between the ideas of the future and the present we have?

The readings for this module will be Elias Herlander Cyberpunk between punks and cyborgs from his Cyberpunk 2.0 (2009) and John Perry Barlow (1996) A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. This module is not about the technology but about the dreams that we had (have?) about the technology. About what we thought the technology would (will) create.

The author Hari Kunzru has a great podcast and his episode When We Were Cyber captures something of what it felt like to be in the beginning of a new and exciting technological phase.

Any explanation as to how we got here, what was important, and what was peripheral is bound to be flawed. In this course the focus will not be on how the technology was made but rather how technology made us feel. However, we cannot ignore technology (in order to talk about what it does, we need to understand what it is). To start with we can ask the question: what is technology? As usual it’s a deceptively simple question. Wikipedia is a great place (and technology) to start. “Technology is the sum of techniques, skills, methods, and processes used in the production of goods or services or in the accomplishment of objectives, such as scientific investigation.”

And if you want to go deeper (who wouldn’t?) check this out…

Martin Heidegger is a fascinating philosopher and you could spend a long time going down the rabbit-hole of his thoughts and writings. But for our purposes we need to develop a working definition of technology and then move on (so much moving on).

Let’s look at a bit of internet technology which is (for this course) almost synonymous with digital technology. A good place to start is by reading Ben Tarnoff How the internet was invented (its a short article).

So what does this technology do to us and to society? The sociologist Manuel Castells is one of the people who has explored the impact on the networked society. Here is a short introduction to his theory of the network society..

Having spent some time with this question it may be fun to browse through these 41 Questions We Should Ask Ourselves About the Technology We Use by L. M. Sacasas in The Questions Concerning Technology (The Convivial Society: Vol. 2, No. 11).

Now that we understand some of the historic, technological, social roots of the digital AND understand what culture is, we are now ready to explore and attempt to analyze an array of digital cultures.

MODULE 4 Performing Identities

Module question: How is mediated identity formed by the technology?

The reading for this module is Waugh (2017) Post-Internet identity

So we are all part of social groups and we all form our identities in relation to these groups. This module will explore the ways in which digital technologies have spawned different ways in which to communicate and demonstrate our belonging or nonbelonging to different cultures and subcultures.

The if you want to be amused to another level check out Rugnetta’s Do You Pronounce it GIF or GIF? which not only presents a third way of pronouncing it but also explains an old joke about how ghoti is pronounced fish. Mind blown. But we digress. The next video explains the central ways in which we wrap ourselves in a piece of digital culture to show who we are. It is a sophisticated form of communication that requires both the sender and receiver to be able to encode and decode the message through their shared culture.

And memes are, in essence, the same issue. I love annoying my teenager by using dated memes and expressions in a wrong context. He almost exploded when I recently dabbed and told him that my syllabus was on fleek. But what is a meme? Where did it come from? Why is it important? What does it have to do with digital culture?

There is obviously nothing in culture that someone will not try to commercialize. Welcome to the concept of clickbait and the attempt to mass produce virality.

MODULE 5 Influencer Culture

Module question: What kind of labor is an influencer doing?

The reading for this module is Wellman (2020) What it means to be a bodybuilder: social media influencer labor and the construction of identity in the bodybuilding subculture

Following on the ideas of virality and the recognition of the massive ability the internet has in reaching people and making people want to share we arrive at the ultimate form of capitalisation of culture: the influencer.

People follow celebrities based off of an admiration for their talent and the work they do through traditional forms of entertainment like movies, sports, or music. People follow influencers for their expertise that is relevant to a goal they want to achieve or a subject they are interested in learning more about such as fitness, fashion, and cooking.

Not All Influencers Are Celebrities…Not All Celebrities Are Influencers, Part 2

An interesting question to ask about influencers is one of authenticity (something they all seem to be concerned with themselves) and whether they are using technology or whether they are products of the system. One way to analyze the influencer would be to ask how much of their labor benefits them?

In a fascinating article Symeon Brown argues that influencers are a form of pyramid scheme both in what they are selling and also in the lifestyle where they are being commodified by someone else. check out Fake it till you make it: meet the wolves of Instagram (or listen to the podcast version). Also Adrienne Matei’s provocative Seeing Is Believing: What’s so bad about buying followers?

“For influencers, authenticity tends to be bound up with aspiration: an image is “true” if it captures and triggers desire, even if the image is carefully and even deceptively constructed. The feeling it inspires in the midst of scrolling is what matters. They draw on the ambiguity between what is real and what is possible. And after all, what could be more inauthentic than an image from an influencer that fails at seeming influential?”

Adrienne Matei Seeing Is Believing: What’s so bad about buying followers?

The HBO ‘documentary’ Fake Famous (2021) was supposed to reveal the truth about influencers:

Fake Famous explores the meaning of fame and influence in the digital age through an innovative social experiment. Following three Los Angeles-based people with relatively small followings, the film explores the attempts made to turn them into famous influencers by purchasing fake followers and bots to “engage” with their social media accounts.

https://www.hbo.com/documentaries/fake-famous

Naomi Fry’s write up about the video “Fake Famous” and the Tedium of Influencer Culture is an interesting read as is Tarpley Hitt’s ‘Fake Famous’ Is HBO’s Lame Attempt at Mocking Influencer Culture

The film’s disdain for its subject matter is palpable—often for good reason, but at times, to an extent that obscures Bilton’s point. At its crux, Fake Famous is about the incentive structure of social media—a system set up by titanic corporations that encourages people to lie, dissuades others from pointing it out, and ensures the rest keep scrolling. And yet the narrative’s focus on people who take advantage of it, who get trapped in it—the protagonists, but also the (mostly) girls that make up its selfie montages or TikTok clips—often lays blame at the feet of users. The camera seems to finger-wag at whatever moral failure has consumed today’s youth, while invoking a vague nostalgia for earlier times.

The film is not really attempting to reveal the problem but actively takes part in the exploitation of technology users while ignoring the role of the economics of influencer marketing.

Aside from the economics of marketing picking and promoting certain types of people worthy of influence in certain ways there is also the issue that this form of marketing can circumvent important consumer safeguards as, for example, explained in The latest Instagram influencer frontier? Medical promotions by Suzanne Zuppello.

So the interesting part about influencers is that they don’t actually have to tell the truth. In advertising you (sort of) have to tell the truth but if an influencer says something its opinion – even though we know its actually advertising, right? This is a great article about the abs-influencer (because of course there are) Will Vin Sant leave you jacked or scammed? Ads starring the ubiquitous ab influencer are everywhere you turn online. But a growing number of fitness experts — and consumers — say that what he has to offer is rather weak.

“My fitness bullshit detector is a finely-tuned machine at this point,” he writes. “A lot of the claims that [Vin Sant] made were simply either lies, mistruths, half-truths, embellishments or unsupported by any evidence — scientific or otherwise. The sad truth is that someone promising rapid results will sell more product, even if their claims are utterly unfounded. The average person just buys based on emotion, not actual information. If they put a handsome guy like Vin Sant in the advertisement and promise massive results, people will buy, even if the actual program is poorly put together.”

MODULE 6 Digital Fitness Culture

Module question: Is fitness technology healthy?

Reading: Toner (2018) Exploring the dark-side of fitness trackers: Normalization, objectification and the anaesthetisation of human experience

My guess is that like most people you think of bodybuilding (and even fitness) as something new. Did you know that the “worlds first” bodybuilder, Eugen Sandow, was born in 1867, invented the word bodybuilding, and held the worlds first bodybuilding contest in 1901 (one of the judges was Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes!).

One of the first dietitians was doctor George Cheyne (born 1672). He was the origin of the health trend of putting himself through an ordeal, gaining health and then writing a popular book for others: His “An Essay of Health and Long Life” was published in 1724.

Even yoga has a less than honest past. According to yoga scholar Mark Singleton it was the Swedish gymnastics pioneer Pehr Henrik Ling (1776–1839) who devised a system of gymnastics which shaped the development of modern yoga as exercise in the Western world.

Enough with the fun facts!! The purpose of this module is to explore the ways in which digital technology in the form of devices and platforms has changed the culture of exercise. Naturally the connection between technology and exercise has always been strong – everything from home workout gear (and their marketing via television), to workout tapes via the vhs boom have made sure that the link between technology and exercise is strong and clear. I mean just read Suzannah Showler’s essay on the Kettlebell: The home-gym staple is a talisman of strength and stability amid general disaster (or listen to it, the audio link on same page) to get a further idea of the connection between culture and equipment.

As many of you know I research and teach privacy and surveillance questions and from this perspective the fitness devices we use are an interesting form of surveillance. Chris Gilliard and David Golumbia (2021) cover this point in their excellent essay Luxury Surveillance: People pay a premium for tracking technologies that get imposed unwillingly on others (audio link on same page)

Internetting has done an excellent episode on the dark side of internet male fitness, its well worth watching.

The connection between working out and obsessive behavior is nothing new but we could argue that fitness apps and platforms have taken this to the next level. One of the largest workout platforms is Strava, “…an American internet service for tracking human exercise which incorporates social network features. It is mostly used for cycling and running using GPS data.” (Strava, Wikipedia) Rose George has a great take on the cultural significance of strava Kudos, leaderboards, QOMs: how fitness app Strava became a religion by Rose George (audio version).

It seems like every company is trying to brand itself as a tech company. Including: the stationary bike company Peloton Is Peloton a Fitness Fad or a Tech Company? this podcast episode explores this expanded definition of “tech company” and what it means for the changing the fitness sector. For more on what Peleton has done listen to I Want to Ride My Internet-Enabled Bicycle: The Peloton Story. It’s connection to the pandemic is fascinating. All our technology should raise the question, so here is What does your Peloton know about you? by Emma McGowan.

Listen to this podcast episode on The Future of Womens Fitness Culture with Madison Magladry & Cecilie Thøgersen-Ntoumani.

I want to close with this quote about what fitness wearbles do:

Wearables sell the “cruel now” of perpetual training and constant maintenance with gamification-based incentive strategies. These posit bodily reserves not as exhaustible but as essentially infinite, easy to top up or restore through sheer force of will. Rather than make the ineffable qualities of bodily movement knowable or understandable in all their complexity, the interface design of health and fitness tracking apps rely on representation and abstraction. These interfaces ape the design aesthetics of the dashboard, using it as a visual shorthand for functionality, control, and performance. The dashboard is positioned as the site through which physical activity acquires significance and meaning; it becomes a prophetic space in which the “self” may discover truths about the mysterious “body.”

Selfwork: How fitness technologies turn the body into an investment property

MODULE 7 Hacker, Maker & Consumer Culture

Module question: What is digital consumption?

Reading: Miller (2020) How Modern Witches Enchant TikTok: Intersections of Digital, Consumer, and Material Culture(s) on #WitchTok

Our contemporary attitudes to consumption, our consumption practices and our consumption desires, have developed alongside the historical development of capitalism as a mode of production. Put simply, consumerism is the capitalist version of consumption; it is a particular historical mode of consumption unique to this mode of production. Consumerism is not, therefore, just consumption, it is increasingly a way of life, producing a sense – what Gramsci would call a ‘common sense’ (1971) – that who we are is defined and expressed through the commodities we consume. Consumerism is a practice that seeks to define people first and foremost as consumers. Moreover, it is a way of life that is dependent on more of the same – i.e. more capitalism.

John Storey (2017) Theories of Consumption p 103-104

Neuroscience Terry Wu explains why we shop and he also gives some great tips for how to gain control over the shopping reflex.

The human brain is not a thinking machine that feels, it’s a feeling machine that thinks. Humans have this innate desire to seek a sense of control. Driven by our strong emotions, we stop making rational decisions when it comes to buying. We buy products simply because we want to gain a sense of control. At the same time, our innate desire to seek instant gratification drives us to buy more and more.

3 brain hacks to control your Amazon addiction (from a neuroscientist)

Is ownership more than buying something? Buying is a legal process in which we transfer property from one person to another. But owning something is more than just holding legal possession of the thing (lawyers may disagree, but that is their limited world view). Think about your phone. How many were made? How many are similar to it? Sure the fact that you bought it makes that individual artifact legally yours but really its use, content, and decoration is what marks it out as yours.

In the not so distant past the manufacturers/sellers interest in a product ended at the sale. What we did with our stuff was interesting to them (and especially not their responsibility if anything went awry). This still applies to many products but a growing amount of products are very interested in both being part of our user experience and even maintaining control of what we do with our stuff. Rachel Huber has written a fascinating and frightening article about the rise of tracking in the fashion industry where the collection of data about our clothes, wardrobes, and bodies in relation to their brand value is on the rise. From Clothing as Platform: Garments have always been a social media, but adding tracking sensors brings it under more direct corporate control

Companies such as Arianee, Dentsu and Evrythng also aim to track clothes on consumers’ bodies and in their closets. At the forefront of this trend is Eon, which with backing from Microsoft and buy-in from mainstream fashion brands such as H&M and Target, has begun rolling out the embedding of small, unobtrusive RFID tags — currently used for everything from tracking inventory to runners on a marathon course — in garments designed to transmit data without human intervention.

https://reallifemag.com/clothing-as-platform/

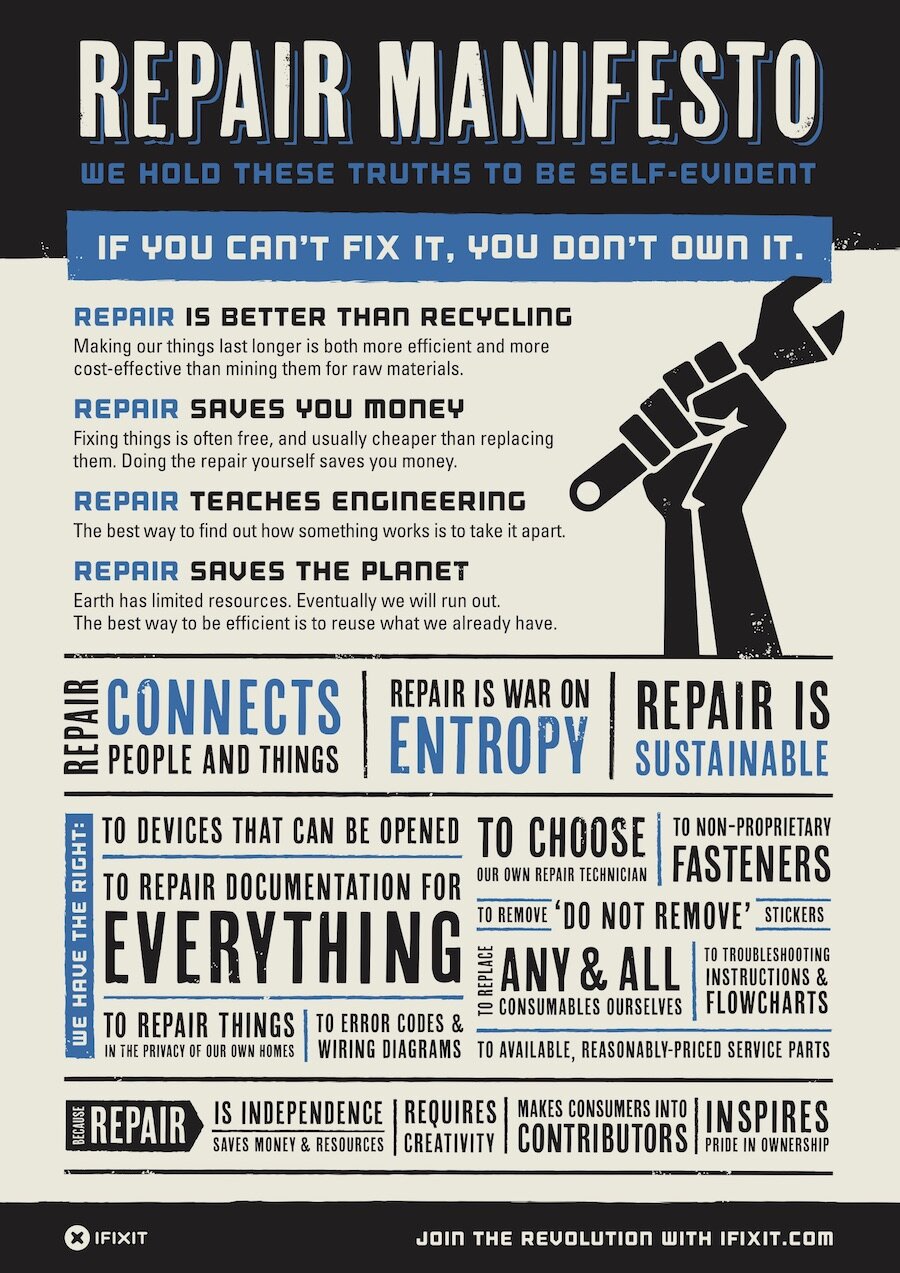

Unsurprisingly? There are movements struggling against this tracked, branded, consumerist, disposable culture and they have different roots. We see a coming together of disparate groups of environmentalists, privacy advocates, labor rights advocates, human rights activists, DIY enthusiasts and tinkerers.

We could even argue that the resurgence of crafting and interest in analog (vinyl, pencils etc) is another strand of this direction. Digital technology gives us the platform to share the ideas, processes, and results (and not just as a Pinterest board, but if you enjoy Pinterest, then check out this Ikea hacks board to get an idea where this is going.

In North America, there was a DIY magazine publishing niche in the first half of the twentieth century. Magazines such as Popular Mechanics (founded in 1902) and Mechanix Illustrated (founded in 1928) offered a way for readers to keep current on useful practical skills, techniques, tools, and materials. As many readers lived in rural or semi-rural regions, initially much of the material related to their needs on the farm or in a small town.

By the 1950s, DIY became common usage with the emergence of people undertaking home improvement projects, construction projects and smaller crafts. Artists began to fight against mass production and mass culture by claiming to be self-made. However, DIY practices also responded to geopolitical tensions, such as in the form of home-made Cold War nuclear fallout shelters, and the dark aesthetics and nihilist discourse in punk fanzines in the 1970s and onwards in the shadow of rising unemployment and social tensions.

Wikipedia Do It Yourself

The ability to modify and repair has always been around but it requires knowledge (remember how technology was more than the thing but also knowledge of the thing?) The digital platforms both attempt to control more and more of or lives (DRM) – but also provide an unparalleled resource for enabling self help. And what a range it is! From the simple howto’s for example the Dad, How do I channel to the increasingly exotic build your own backyard well for free water or sewage system!

So in an interesting (but unsurprising) turn of events the spread of repair information runs parallel to companies actively attempting to make sure you cannot repair their products. This has sparked some outrage and created the right to repair movement which argues if you own something you should have the right to take it apart, repair it, or take it to the repairman of your choice (how Free Software, right?). These groups advocate for

- Make information available: Everyone should have reasonable access to manuals, schematics, and software updates. Software licenses shouldn’t limit support options and should make clear what’s included in a sale.

- Make parts and tools available: The parts and tools to service devices, including diagnostic tools, should be made available to third parties, including individuals.

- Allow unlocking: The government should legalize unlocking, adapting, or modifying a device, so an owner can install custom software.

- Accommodate repair in the design: Devices should be designed in a way as to make repair possible.

This report from Open Markets is interesting for more background on the right to repair: Fixing America: Breaking Manufacturers’ Aftermarket Monopoly and Restoring Consumers’ Right to Repair (Hanley, Kelloway & Vaheesan, 2020)

Paradoxically, the rise of digital platforms has also pushed the rise of hackerspaces, community oriented workspaces where people with common interests, such as computers, machining, technology, science, digital art, or electronic art, can meet, socialize, and collaborate. You should check out NYC Resistor in Brooklyn, MakerSpace NYC in Brooklyn and on Staten Island or find one near you.

The maker movement has also formed part of a type of activism (and not just against consumerism) Garnet Hertz Disobedient Electronics offers a great example of this. He writes:

1. Building electronic objects can be an effective form of social argument or political protest. 2. DIY, maker culture and local artisinal productions can have strong nationalist and protectionist components to them – in some senses, populism can be seen as the rise of the DIY non-expert. 3. Critical and Speculative Design (Dunne & Raby) are worthwhile approaches within industrial design, but perhaps not adversarial enough to reply to contemporary populist right-wing movements (Brexit, Trump & Le Pen). Questions like “Is it moral to punch Nazis in the face?” should be answered with smart alternatives to violence that are provocative pieces of direct action. 4. If we are living in a post-truth time, we should focus on trying to make progressive arguments and facts more legible and engaging to a wide and diverse audience. 5. The fad of ‘Maker Culture’ is over. Arduinos and 3D printers are fascinating things, but the larger issues of what it means to be a human or a society needs to be directly confronted.

MODULE 8 Participatory Culture and Subversive Sharing

Module question: Who controls our stories and knowledge?

Reading: Peterson-Reed (2019) Fanfiction as Performative Criticism: Harry Potter Racebending

The internet was an amazing innovation but it was not broadly used by a large group of people until the WWW came along and (arguably) made it easier for everyone to join in. In order for this to work home PCs and modems had to develop into basic household goods and we had to enable pricing of the use not by the minute or the download. But AFTER all that the internet and especially the web became a huge hit!

The Web, is an information system where documents and other web resources are identified by Uniform Resource Locators, which may be interlinked by hyperlinks, and are accessible over the Internet. The resources of the Web are transferred via the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), may be accessed by users by a software application called a web browser, and are published by a software application called a web server. The World Wide Web is not synonymous with the Internet, which pre-dated the Web in some form by over two decades and upon which technologies the Web is built. The Web was invented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989, he made the first web browser in 1990 and it was released to the general public in August 1991. The Web began to enter everyday use in 1993–4, when websites for general use started to become available.

World Wide Web, Wikipedia (not exact quote)

As the use of the Web exploded it seemed like everyone and every company needed to be online. This caused rampant speculation and investment (the dot-com boom) followed by the bursting of the bubble (Between 1995 and its peak in March 2000, the Nasdaq Composite stock market index rose 400%, only to fall 78% from its peak by October 2002. Wikipedia dot-com bubble) Enthusiasm for the Web cooled down and did not begin to rise again until the period of “social media” or Web 2.0, a term popularized at the first O’Reilly Media Web 2.0 Conference in late 2004. This change was about the focus on interactive (hence “social’) websites over websites limited to passive viewing (of course we can argue about the terms passive and active but you get the gist).

This phase in the web was also termed participatory culture. Henry Jenkins defines this as a culture with:

- With relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement

- With strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations with others

- With some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices

- Where members believe that their contributions matter

- Where members feel some degree of social connection with one another (at the least they care what other people think about what they have created).

Not every member must contribute, but all must believe they are free to contribute when ready and that what they contribute will be appropriately valued. Therefore it is a culture with relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices.

Participatory culture covered a wide array of online phenomena from blogs and Wikipedia to Instagram and even Reddit. There was another form of sharing that the online world supported, one that was perceived as a grave threat to the copyright industry. Piracy, or the practice of distributing copyrighted content digitally without permission. The internet was (and is) an amazing tool for sharing. And one of the things that people wanted to share (and still do) was cultural products. Naturally some creators were threatened by this and others invigorated, as Cory Doctorow writes “my problem isn’t piracy, it’s obscurity”

In the early phases of participatory culture it seemed like everyone wanted user/customer participation. Since then there has been somewhat of a participatory fatigue (Porlezza, 2019). He writes

In the meantime, many newsrooms have even decided to further limit the possibilities of holding the media to account by shutting down user comments or closing newsroom blogs due to participation inequality or challenging phenomena such as trolls, incivility, or hate-speech. Therefore, many newsrooms show a participatory fatigue rather than a participatory culture.

From Participatory Culture to Participatory Fatigue: The Problem With the Public

Subversive Sharing

For most users the ability share files revolutionary. Check out the Napster documentary. Also Wikipedia has a great timeline of file sharing.

While the industry fought back and began massive legal actions to stop piracy. These had little effect until streaming services became established. Arguably Spotify ‘stopped’ music file sharing and Netflix did the same for video files. But piracy did not stop because these services came along and there are many arguments that the streaming services hurt producers’ revenue and there are interesting arguments that streaming services change what and how we consume.

As the number of streaming video services (and therefore the cost) have begun rise there seems to have been a rise in the use of online piracy again.

Readings Kelty, C. M. (2012). From participation to power. In The participatory cultures handbook (pp. 40-50). Routledge. Breakey, H. (2018). Deliberate, principled, self-interested law breaking: The ethics of digital ‘piracy’. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 38(4), 676-705.

MODULE 9 Digital Public Sphere

Module question: Why does truth matter in democracy?

Reading: Chambers (2021) Truth, Deliberative Democracy, and the Virtues of Accuracy: Is Fake News Destroying the Public Sphere?

The german word Öffentlichkeit refers to publicness but has come to be translated as the public sphere. This is the space where public life (as opposed to private life) happens. You can think of it both as the arena of politics (for example the senate floor) but also those spaces in public that social interaction occurs. In the latter sense our classroom at Fordham is part of Öffentlichkeit even if the building is private. The privateness does matter though since there are legitimate arguments that for a space to truly be a public sphere it must have close to zero barriers to entry.

Other fun german words are Luftschloss (air castle) unrealistic dream or desire, Kummerspeck (grief bacon) or the weight gained by eating when sad, and Fremdschämen (stranger embarrassment?) the painful cringey feeling when you watch see another person create an embarrassing situation.

The term public sphere was originally coined by German philosopher Jürgen Habermas who defined the public sphere as “made up of private people gathered together as a public and articulating the needs of society with the state”. Gerard A. Hauser defines it as “a discursive space in which individuals and groups associate to discuss matters of mutual interest and, where possible, to reach a common judgment about them”. Nancy Fraser compares the public sphere as “a theater in modern societies in which political participation is enacted through the medium of talk” and Robert Asen adds it is “a realm of social life in which public opinion can be formed”.

When the internet came along it was immediately seen as an improved public sphere since ‘anyone’ could join the discussion and that you could do so without disclosing your age, race, gender, etc. But Habermas himself was not as convinced, and since then the discussion of the role of technology in the public sphere has been extensively debated. Check out Jodi Dean’s article Why the Net is not a Public Sphere

The first question (and oddly one of the earliest questions about the internet) that needs to be addressed is whether the internet is a public space? And if so, then what kind of public space is it? Check out Mike Rugnetta’s exploration of this question.

To make things more difficult (or more interesting) is the internet one thing at all? The more likely thing is that we have many internets, many facebooks, many instagrams. What I mean by this is that it is partly pointless to talk about one instagram, one reddit, one ticktock since no two users experience the same content. Is this difference important?

Well in part these differences have led to the rise to misinformation, fake news, echo chambers ultimately seemingly parallel forms or reality. Check out this example where a flat earther spent $20000 to prove that the world was round and therefore believes that the experiment is wrong (not their assumption that the world is flat).

Listen to Helen Margetts, head of the Oxford Internet Institute, talks to the Financial Times’ Madhumita Murgia about fake news, echo chambers, big data and why we need more research to be able to combat the “pathologies” of the internet. https://www.stitcher.com/show/ft-tech-tonic/episode/political-disruption-and-the-internet-49584814

But its not all bad. The internet has enabled far more participation check out Youth, New Media, and the Rise of Participatory Politics (Kahne et al 2021).

So the problem is that these are not public spaces, but they are privately owned public spaces (POPS). As we all migrate our lives to these POPS we increasingly become dependent on the ideologies and rules that the company supports. A great documentary by Frontline, The Facebook Dilemma, Parts I & II, Season 37, Episodes 4 & 5. October 29-30, 2018. Part I: Facebook’s promise was to create a more open and connected world. FRONTLINE finds that multiple warnings about the platform’s negative impact on privacy and democracy were eclipsed by Facebook’s relentless pursuit of growth. Part II: A series of mounting crises at Facebook, from the company’s failure to protect users’ data, to the proliferation of “fake news” and disinformation, have raised the question: How has Facebook’s historic success brought about real-world harm? FRONTLINE traces a series of warnings to the company as it grew into a global empire.

MODULE 10 Activist Culture

Module question: Why tools matter for the activist?

reading Milan & Barbosa (2020) Enter the WhatsApper: Reinventing digital activism at the time of chat apps

What is activism? Who is an activist? It is easy to stand in the shadow of the greats (Gandhi, MLK) and look at the historic social movements (emancipation, suffrage) and feel quite insignificant. It is easy to diminish all acts other than the grand revolutions that we read in history books. But to do so would be to miss the point. Before the revolution there were many acts of resistance and activism that created the space for the large things to come.

In Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance, James C. Scott writes:

“Everyday forms of resistance make no headlines. Just as millions of anthozoan polyps create, willy-nilly, a coral reef, so do thousands upon thousands of individual acts of insubordination and evasion create a political or economic barrier reef of their own. There is rarely any dramatic confrontation, any moment that is particularly newsworthy. And whenever, to pursue the simile, the ship of state runs aground on such a reef, attention is typically directed to the shipwreck itself and not to the vast aggregation of petty acts that made it possible. It is only rarely that the perpetrators of these petty acts seek to call attention to themselves. Their safety lies in their anonymity. It is also extremely rarely that officials of the state wish to publicize the insubordination. To do so would be to admit that their policy is unpopular, and, above all, to expose the tenuousness of their authority in the countryside—neither of which the sovereign state finds in its interest.19 The nature of the acts themselves and the self-interested muteness of the antagonists thus conspire to create a kind of complicitous silence that all but expunges everyday forms of resistance from the historical record.”

In the technology mediated world we have now both the ability to participate in new ways and also a world that is becoming increasingly activist. What happens then is that we both encourage participation but tend to denigrate online acts as slacktivism or self agrandisement. The UNICEF Global Insight digital civic engagement writes in its conclusion

In other words, in order to support children and young people to participate in civic life through online engagement, we need to understand what they care about and what motivates them to speak out. In turn, we need to better understand whether current support to youth civic engagement — digital, blended, or offline — properly reflects these motivations. Finally, we cannot choose to support young people in their quest for online political or civic expression, without paying attention to the context of the digital media ecosystem, including the opportunities and risks involved.

UNICEF Global Insight digital civic engagement (2020)

Corinne Segal (2017) Stitch by stitch, a brief history of knitting and activism

Jackson & Foucault Welles: Hijacking #myNYPD: Social Media Dissent and Networked Counterpublics Journal of Communication

Readings: Paige Alfonzo (2021) A Topology of Twitter Tactics: Tracing the Rhetorical Dimensions and Digital Labor of Networked Publics. SelVega, S. R. (2017). Selfless Selfie Citizenship: Chupacabras Selfie Project. In Selfie Citizenship (pp. 137-147). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

MODULE 11 Neo-Luddite Culture

Module question: How to maintain control in a technological world?

Reading: Steven Jones (2016) Against Technology: From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism, chapter 1.

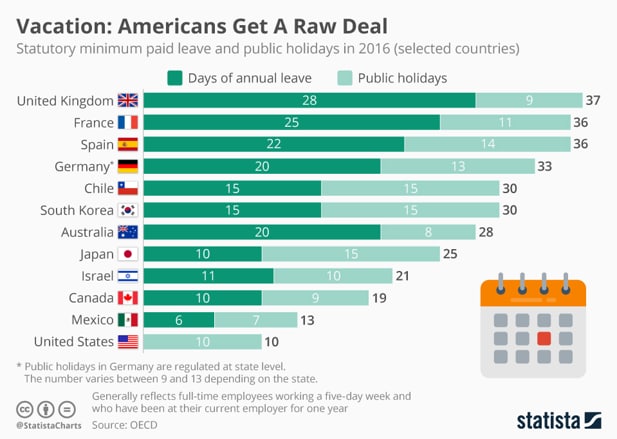

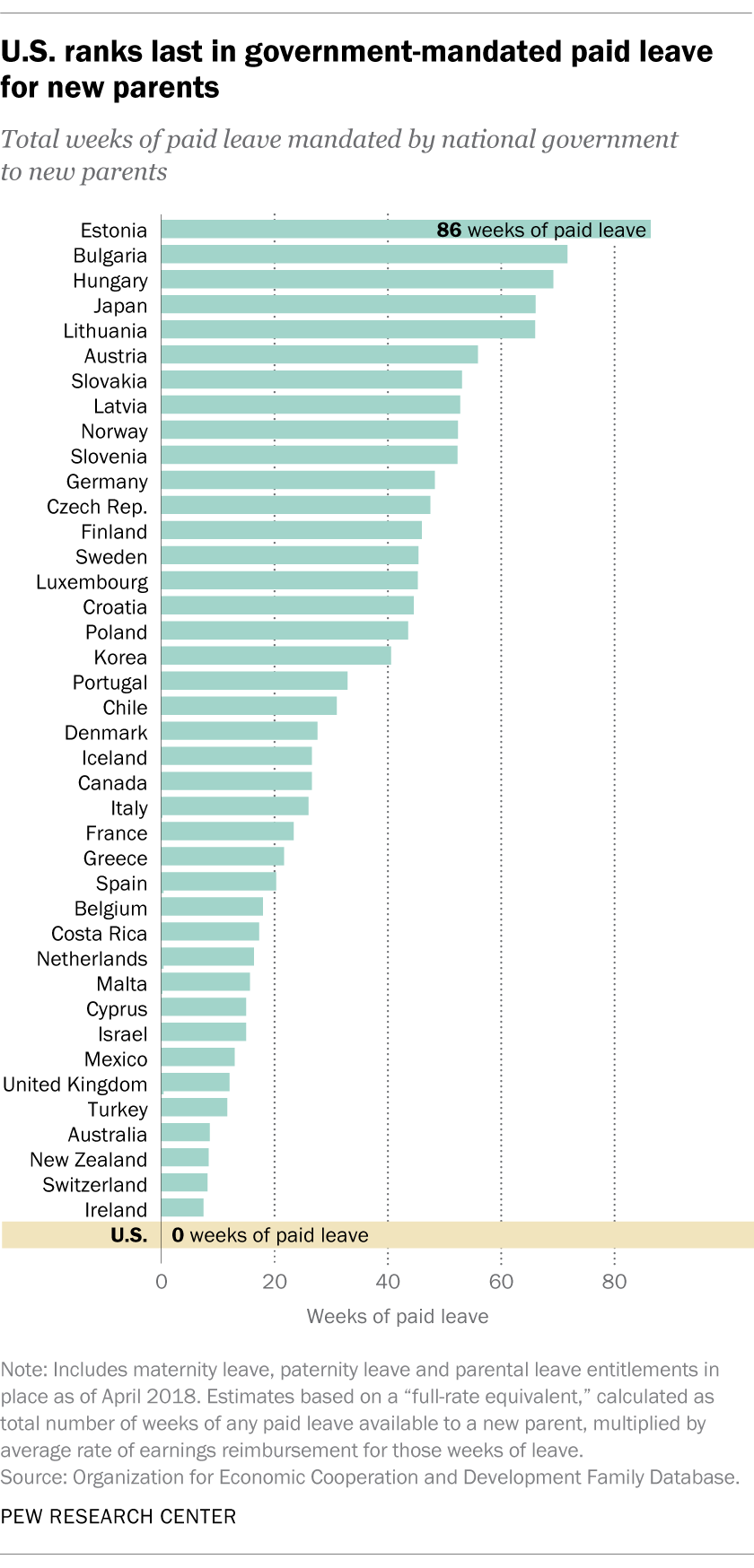

In 1930 the economist John Maynard Keynes once wrote an essay titled “Economic Possibilities For Our Grandchildren” in which he argued that people might be working just 15 hours a week. It was not that the technological advances stopped so why are we working as much as we do? (listen to a short Planet Money figure out what went wrong).

The culture of overworking (and also bragging about it) is a growing worldwide system

New studies show that workers around the world are putting in an average of 9.2 hours of unpaid overtime per week – up from 7.3 hours just a year ago. Co-working spaces are filled with posters urging us to “rise and grind” or “hustle harder”. Billionaire tech entrepreneurs advocate sacrificing sleep so that people can “change the world”. And since the pandemic hit, our work weeks have gotten longer; we send emails and Slack messages at midnight as boundaries between our personal and professional lives dissolve.

Bryan Lufkin (2021) Overwork culture is thriving

It may be worldwide but it also seems to be cultural and America is at the top of the cult of work its like we are against leisure time.

In addition to working long hours (with comparatively no benefits) jobs are less lucrative than before. While minimum wage has been basically stagnant the cost of living has increased. This means that a worker in the 60s, 70s, 80s (etc) had more spending power and could survive longer on their salary than before.

OK, but where is the digital you ask? Well this is where the gig economy comes in. The gig economy increases the level of precarity among workers but often it is touted as “working for yourself” or “being your own boss” Or as Wikipedia describes it “Gig workers have high levels of flexibility, autonomy, task variety and complexity.” This sounds great and it probably is great if you are at the top of a professional, in-demand, knowledge intense gig. But I doubt this is how the lower end of the scale feel.

Put it this way. If it was such a great opportunity then we would be offering a lot more perks and owners would not fear labor unions.

We could also spend a great deal of time looking at the ways in which workplace surveillance has become a boom market. With a whole range of tools workers on all levels are being spied upon to an ever increasing degree. Tools such as Zoom and Slack (I know, I know, I’m sorry… we can talk about it) are tools of surveillance and control. Once again we see that they are tools marketed as freeing and creative but in reality they are just the next step in Taylorism. Indeed technologies such as these move the workplace into the private sphere and into what little private time we have. It also changes our perceptions of each other- check out Autumm Caines (2020) The Zoom Gaze: Video conferencing offers an illusory sense of unilateral control over conversations or listen to audio version, link on the same page.

There are, of course, movements against these attempts to take what little time and space we have left. We see the rise of neo-luddism as a form of challenge to the digitized worker:

A neo-Luddite movement would understand no technology is sacred in itself, but is only worthwhile insofar as it benefits society. It would confront the harms done by digital capitalism and seek to address them by giving people more power over the technological systems that structure their lives.

Jason Sadowski (2021) I’m a Luddite. You should be one too

And there are increasing attempts to create more viable working conditions around gig work. Its going to be a long process.

Before we leave this I also want to talk about the forms of labor that “dont count”. Check out Tamara Kneese (2021) Home Spun: Etsy sellers, parent bloggers, and other practitioners of feminized platform labor are tech workers too

MODULE 12 Memory & Forgetting in Obsolescence culture

Module question: Does it matter if digital tools effect our memory?

Reading: van Dijck (20o4) Memory Matters In the Digital Age

The coolest phone I ever owned (and I have owned many) was the titanium shelled Nokia 8910. The compact little device slid open with a pleasing sound when you pressed the two silver buttons on the side – it was elegant.

But as it was released in 2002 it really did not have the ability to compete with the soon to be ubiquitous smartphones. It still functioned but it no longer served the my purposes and its slim little design got left in a drawer.

5 forms of obsolescence

Aside from the nostalgia my old Nokia, is a great example of one form of obsolescence: (1) When the users choose to use something that offers them a better solution to their overall needs. (2) This is a different form of obsolescence than when the technology cannot function anymore. The latter may occur because the technical environment surpasses its capacity (old computers do not have the processing power to handle present day software), or it could occur when legal changes make the product obsolete (as with the incandescent lightbulbs in Europe). The next form of obsolescence is (4) when manufacturers take a product out of production, this happened in 2018 when Canon stopped the production of film cameras after 80 years.

Planned obsolescence through policy is the practice of designing a product with an artificially limited useful life or a purposely frail design, so that it becomes obsolete after a period of time. The documentary below is all about the infamous Phoebus cartel, that engineered a shorter-lived lightbulb and gave birth to planned obsolescence – there a great write-up about the cartel and its ongoing effects here.

As a society we have a system of sorts to deal with the past. Once our stuff has become obsolete we discard it, but over time we move that stuff into the realm of past culture and attempt to preserve it in museums. Attempting to save digital devices or products has challenges of its own.

Preserving the past is a technically difficult process. For example: Given optimal conditions paper can last 100s of years, magnetic media (tape) also deteriorates naturally with typical shelf lives between 10 and 20 years, CDs & DVDs last 10 or 25 years or more. Most storage formats decay and without proper care will not survive. When we look at paper books the older books are in better condition because there is less acid in the paper. So we have copies of the Gutenberg bible from 1454 while books from the 1940s are falling apart (naturally it depends on how well the book has been cared for while it was in use and a bunch of other factors). Among the older/oldest books in preservation are books that were not printed on paper as clay, stone, and metal has a longer lifespan.

Aside from merely storing/preserving the object we also need to be able to access and interpret the content.

Therefore when we discovered the 650 baked clay tablets from before 1200 B.C. inUgarit, on the coast of Syria we knew there was human communication happening. But because we are able to read the cuniform we have learned much about the businessman, Urtenu, who ran a trading firm that conducted business on behalf of the state. The ability to read his letters, ledgers, administrative texts, and diplomatic missives tell us a great deal about him, his life and society.

Between 1200 and about 1185 B.C., Urtenu’s correspondence took on a more ominous tone. Polite requests for help turned into increasingly desperate pleas as severe drought and famine began to upend life in the kingdoms and city-states around Ugarit. The tablets speak of biru, “hunger” in the Akkadian language, which was widely spoken in the Levant, spreading across the landscape. “If there is any goodness in your heart, then send even the remainders of the [grain] staples I requested and thus save me,” pleads a Hittite official. Food shortages were becoming dire. “In the land of Ugarit there is a severe hunger. May my Lord save it, and may the king give grain to save my life…and to save the citizens of the land of Ugarit,” wrote Ugarit’s king Ammurapi (ca. 1215–1190 B.C.) to the Egyptian pharaoh Seti II, who ruled from about 1200 to 1194 B.C.

The Ugarit Archives

Compare this to the fact that I have, somewhere in the recesses of my harddrive, old powerpoint presentations that I cannot view because the formats have changed. Obviously the presentations are hardly of equal importance but it is a great example of how it is not enough to save, we need to save the equipment to access and read what we have saved.

Another amazing piece of trivia in this area is the complaint letter of Ea-nasir which can be seen in the British Museum

The complaint tablet to Ea-nasir (UET V 81)[1] is a clay tablet that was sent to ancient Ur, written c. 1750 BC. It is a complaint to a merchant named Ea-nasir from a customer named Nanni. Written in Akkadian cuneiform, it is considered to be the oldest known written complaint. It is currently kept in the British Museum.[2][3]

Ea-nasir travelled to Dilmun to buy copper and returned to sell it in Mesopotamia. On one particular occasion, he had agreed to sell copper ingots to Nanni. Nanni sent his servant with the money to complete the transaction.[4] The copper was sub-standard and not accepted. In response, Nanni created the cuneiform letter for delivery to Ea-nasir. Inscribed on it is a complaint to Ea-nasir about a copper delivery of the incorrect grade, and issues with another delivery;[5] Nanni also complained that his servant (who handled the transaction) had been treated rudely. He stated that, at the time of writing, he had not accepted the copper, but had paid the money for it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complaint_tablet_to_Ea-nasir

There are several projects aimed at preserving our data some like the Internet Archive aimed at “building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form. Like a paper library, we provide free access to researchers, historians, scholars, the print disabled, and the general public.”

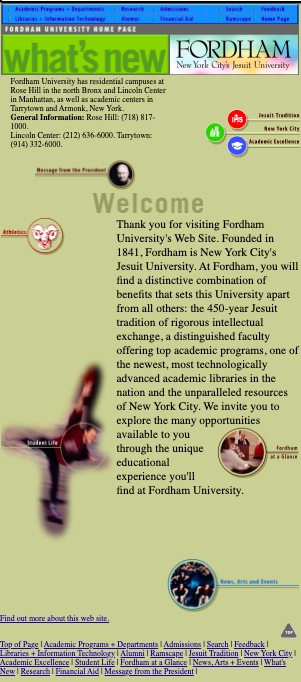

Fordham.edu 1998

Without the efforts of the Internet Archive we would not be able to see what the web looked like in its earliest days. This is a resource that is invaluable for researchers and also a fun thing to check out via the WayBack Machine.

The Internet Archive also has more than web pages. Casey Patterson uses it in his research and teaching…

Instead of expecting students to buy several books, and without the ability for them to check out books in a library, Patterson turned to the Internet Archive. Patterson found works of Black critics such as Toni Morrison and C.L.R. James and their writings about 19th century authors Edgar Allen Poe and Herman Melville to use in class. He downloaded classics including Moby Dick and Huckleberry Finn to the Canvas learning management system and made them immediately available to students.

Another project of the Internet Archive is the Great 78 Project. The brainchild of the Archive’s founder, Brewster Kahle, the project is dedicated to the preservation and discovery of 78rpm records. Read How The Great 78 Project is saving half a million songs from obscurity.

Other projects work to save the devices check out the small and quirky Museum of Obsolete Media. And then there is the really interesting question of what happens to all our digital stuff when we die? Is it lost forever? Where do the family photos end up if they are all digital? Who makes sure that the stuff we dont want to be found ‘disappears’ when we do? If we don’t pay attention to our personal histories then what will become of our collective history?

A pile of trash, especially of my own creation, has an abject allure. It shimmers between debris to be forgotten, discharged into nonspace, and an accumulation to be prodded and appraised, as though shelved in a thrift store. I infuse my trash pile with a vitality that contradicts its inertness: Each discarded object issues a call that is not just an echo of its forgone human utility but something wholly its own.

Ana Cecilia Alvarez (2017) Trash Life: Both landfills and data storage facilities are teeming with threatening vitality

Aside storage and preservation there are also projects attempting to preserve data and culture for the very long term. These projects face a whole array of difficulties: Storing Digital Data for Eternity. A fascinating organization attempting to think long term is the Long Now Foundation.

One final thought before we leave this topic. We know that the nuclear waste we produce today will be lethal for many thousands of years, so how do we warn beings in 10000 years to leave it alone? the more you think about it the more complex the problem gets. Any signs must not decay, the message on them must be comprehensible to future cultures to whom we may have no common reference points.

MODULE 13 Play Culture

Module question: Is it harmful if work becomes play? And play becomes work?

Reading: Woodcock & Johnson (2018). Gamification: What it is, and how to fight it.

As life imitates strange games through quantified self or the darker This Is Not a Game: Conspiracy theorizing as alternate-reality game (Jon Glover 2020) and games become closer to forms of labor The Gamification of Games: When play becomes chiefly about data collection (Ulysses Pascal 2020). The distinctions between what is play and what isn’t becomes very blurry.

To a certain extent we can identify the subculture through the terminology. We can ask if someone they are a gamer and this will identify certain types of individuals within play culture. Then we can dig deeper and ask endless questions as to how much gaming, what type of games etc This type of questioning can be seen as a form of gatekeeping. Are you really a gamer? and do you qualify as the right type of gamer? However, the problem with this is that it becomes a form of elitism. Are you more of a gamer if you play on a console or a mobile device? If you play with others or alone? Is someone who plays hours of solitaire a gamer? Would it make a difference if it was played on a laptop, smartphone or analog? if it makes no difference can we even talk about game culture? Wikipedia has an entry for video game culture but not for game culture. Even though almost nobody plays video games anymore.

Another part of game culture (maybe?) is the question of gamification.

Gamification broadly refers to technological, economic, cultural, and societal developments in which reality is becoming more gameful, and thus to a greater extent can afford the accruing of skills, motivational benefits, creativity, playfulness, engagement, and overall positive growth and happiness.

Hamari, J. (2019). Gamification. Blackwell Pub, In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology

With systems such as goals, rewards, and points many fitness apps can be seen as games. They are designed to make exercise more entertaining or less boring but this is done by turning to the rewards systems of games. The mobile game Zombies, run! is an excellent example of this crossover.

In order for gamification to work we have to (as with movies) suspend our disbelief and buy into the process. But it is interesting to think how it could be abused if