For a brief moment I am pleased with myself: I have managed to think of yet another snappy title for my next talk. But part of me always raises the question: Was it too snappy? Am I trying too hard? Should I really be entertaining?

The question as to whether a lecture should be entertaining is a thorny one. If I am boring then I shall send my audience to sleep and nothing will be learned. But if I am entertaining then all that will be remembered is a moderately funny guy talking about something to do with copyright. Everything is balance.

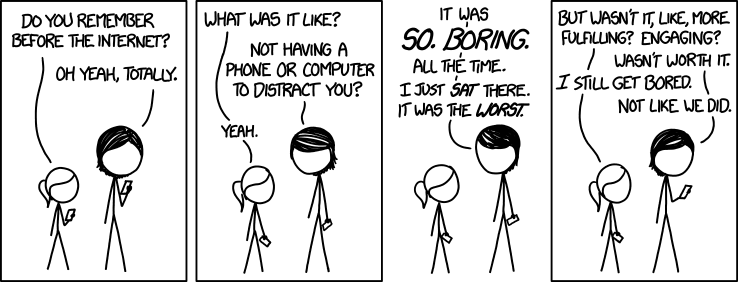

It wasn’t always this way. Audiences, even academic audiences, have begun to expect to be challenged less than before. The skill of sitting and listening actively for hours is disappearing rapidly. Some try to blame it on our gadgets – but I don’t think that’s right. The gadgets are simply the symptom of what is wrong. It is because we are bored that we reach for our gadgets, not the other way around.

The problem is that audiences have begun to believe that the pinnacle of lecturing is something close to the TED talk. It’s a pithy 15 minutes with “take homes” and “solutions” to real live “problems”. Where those who are presented as suffering from a problem are almost immediately presented with a happy solution. It’s basically a sit-com where all the worlds problems must be resolved in between some neatly packaged marketing (preferably barely noticeable product placement).

The love of TED (and its ilk) is almost universal but there are some interesting detractors on the horizon. I really like the brutal comment from Nassim Taleb in Black Swan, where he describes TED as the “monstrosity that turns scientists and thinkers into low-level entertainers, like circus performers.”

Or what about Benjamin Bratton’s anti-TED TED talk which questions “why the bright futures of so many TED talks don’t come true?”, Benjamin Bratton rips the concept and organization apart:

“TED of course stands for ‘Technology, Entertainment, Design.’ To me, TED stands for ‘Middle-brow, Megachurch Infotainment’.

Thomas Frank wrote an article in Salon entitled TED Talks Are Lying To You where he argued that TED is basically an example of the repetition of norms of the attempt to sell the dream of monetizing creativity.

In Why I’m not a TEDx Speaker Frank Swain addresses primarily the economic issues of TED. His beef is that they despite charging around $6000 dollars the speakers are unpayed and so are many of the auxiliary staff. His criticism is that their idea is not novel (talking on stage) and what they essentially do is brand other peoples ideas as theirs. Not stealing, but branding. “And within that manifesto, TED pushes the philosophy that there is value in ideas, but not value in delivering them.”

Returning to Bratton he wrote We need to talk about TED in about the problem with TED’s oversimplification of issues:

Instead of dumbing-down the future, we need to raise the level of general understanding to the level of complexity of the systems in which we are embedded and which are embedded in us. This is not about “personal stories of inspiration”, it’s about the difficult and uncertain work of demystification and reconceptualisation: the hard stuff that really changes how we think.

Of course there is a place for the entertainment of TEDs but the problem is that their underlying philosophy must not be questioned by anyone. What we end up with is a system that does not question the content but is immediately prepared to belittle a talk that is not “kick-ass” or “mind-blowing”. With TED entertainment is king, criticism is seen as small-minded bitterness and the business model is self-congratulatory. This is what cults are like. Martin Robbins The Trouble With TED Talks describes it as a cult-like phenomenon and realizes why it is the way it is:

Ultimately, the TED phenomenon only makes sense when you realise that it’s all about the audience. TED Talks are designed to make people feel good about themselves; to flatter them and make them feel clever and knowledgeable; to give them the impression that they’re part of an elite group making the world a better place. People join for much the same reason they join societies like Mensa: it gives them a chance to label themselves part of an intellectual elite. That intelligence is optional, and you need to be rich and well-connected to get into the conferences and the exclusive fringe parties and events that accompany them, simply adds to the irresistible allure. TED’s slogan shouldn’t be ‘Ideas worth spreading’, it should be: ‘Ego worth paying for’.

And far away from the epicenter, everyday lecturers are pressured into being entertaining for fear of not living up to the nonsensical goals created by an organization that is not about education. University students expect entertainment and are less than happy when they have their values or ideas challenged. They have seen the TED, they want their ego’s stroked and opinions valued over any dry facts that are presented.

Instead of lusting after TED, universities should do what they have always done best: Apply critical thinking, ask annoying hard questions and reward rigor and method over entertainment and customer satisfaction.