In preparation for my course on privacy I asked the hive mind (mainly Twitter & Facebook) for recommendations of films that deal with privacy. I mostly wanted fictional stuff but most of the documentaries are too good not to include (even though I am sure I have missed a lot of documentaries).

The list is by no means complete so please add or send me anything I missed.

You only live once (Lang 1937) Joan Graham (Sylvia Sidney) works as the secretary to the public defender. Unfortunately, she’s fallen madly in love with a criminal by the name of Eddie Taylor (Henry Fonda). Convinced that Eddie is a good man with bad luck, she pulls some strings and gets Eddie released from prison early. The two get married, but while Eddie tries to fly right, he soon discovers he can’t change his nature. His past comes knocking at their door, and the couple is forced to go into hiding.

The Philadelphia Story (Cukor, 1940) This classic romantic comedy focuses on Tracy Lord (Katharine Hepburn), a Philadelphia socialite who has split from her husband, C.K. Dexter Haven (Cary Grant), due both to his drinking and to her overly demanding nature. As Tracy prepares to wed the wealthy George Kittredge (John Howard), she crosses paths with both Dexter and prying reporter Macaulay Connor (James Stewart). Unclear about her feelings for all three men, Tracy must decide whom she truly loves.

Rear Window (Hitchcock, 1954) Sitting in a wheelchair, his leg in a cast, a photographer (James Stewart) spies on courtyard neighbors and sees a murder.

The Conversation (Coppola, 1974) Surveillance expert Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) is hired by a mysterious client’s brusque aide (Harrison Ford) to tail a young couple, Mark (Frederic Forrest) and Ann (Cindy Williams). Tracking the pair through San Francisco’s Union Square, Caul and his associate Stan (John Cazale) manage to record a cryptic conversation between them. Tormented by memories of a previous case that ended badly, Caul becomes obsessed with the resulting tape, trying to determine if the couple are in danger.

All the President’s Men (Pakula, 1976) Two green reporters and rivals working for the Washington Post, Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman), research the botched 1972 burglary of the Democratic Party Headquarters at the Watergate apartment complex. With the help of a mysterious source, code-named Deep Throat (Hal Holbrook), the two reporters make a connection between the burglars and a White House staffer. Despite dire warnings about their safety, the duo follows the money all the way to the top.

Nineteen Eighty-Four (Radford, 1984) A man loses his identity while living under a repressive regime. In a story based on George Orwell’s classic novel, Winston Smith (John Hurt) is a government employee whose job involves the rewriting of history in a manner that casts his fictional country’s leaders in a charitable light. His trysts with Julia (Suzanna Hamilton) provide his only measure of enjoyment, but lawmakers frown on the relationship — and in this closely monitored society, there is no escape from Big Brother.

Brazil (Gilliam, 1985) Low-level bureaucrat Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) escapes the monotony of his day-to-day life through a recurring daydream of himself as a virtuous hero saving a beautiful damsel. Investigating a case that led to the wrongful arrest and eventual death of an innocent man instead of wanted terrorist Harry Tuttle (Robert De Niro), he meets the woman from his daydream (Kim Greist), and in trying to help her gets caught in a web of mistaken identities, mindless bureaucracy and lies.

The Net (Winkler, 1995) Computer programmer Angela Bennett (Sandra Bullock) starts a new freelance gig and, strangely, all her colleagues start dying. Does it have something to do with the mysterious disc she was given? Her suspicions are raised when, during a trip to Mexico, she’s seduced by a handsome stranger (Jeremy Northam) intent on locating the same disc. Soon Angela is tangled up in a far-reaching conspiracy that leads to her identity being erased. Can she stop the same thing from happening to her life?

Gattaca (Niccol, 1997) Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke) has always fantasized about traveling into outer space, but is grounded by his status as a genetically inferior “in-valid.” He decides to fight his fate by purchasing the genes of Jerome Morrow (Jude Law), a laboratory-engineered “valid.” He assumes Jerome’s DNA identity and joins the Gattaca space program, where he falls in love with Irene (Uma Thurman). An investigation into the death of a Gattaca officer (Gore Vidal) complicates Vincent’s plans.

The End of Violence (Wenders, 1997) Producer Mike Max (Bill Pullman) has made a fortune through his gory action flicks, but his own capture at the hands of some thugs causes him to reexamine his role in violent productions. After escaping the crooks, he hides out with a group of gardeners, and eventually decides to drop out of Hollywood and stay with his new protectors. Meanwhile, government surveillance man Ray (Gabriel Byrne) uses a complex network of cameras to spy on Los Angeles, but he is disturbed by his superiors.

The Truman Show (Weir, 1998) He doesn’t know it, but everything in Truman Burbank’s (Jim Carrey) life is part of a massive TV set. Executive producer Christof (Ed Harris) orchestrates “The Truman Show,” a live broadcast of Truman’s every move captured by hidden cameras. Cristof tries to control Truman’s mind, even removing his true love, Sylvia (Natascha McElhone), from the show and replacing her with Meryl (Laura Linney). As Truman gradually discovers the truth, however, he must decide whether to act on it.

Enemy of the State (Scott, 1998) Corrupt National Security Agency official Thomas Reynolds (Jon Voight) has a congressman assassinated to assure the passage of expansive new surveillance legislation. When a videotape of the murder ends up in the hands of Robert Clayton Dean (Will Smith), a labor lawyer and dedicated family man, he is framed for murder. With the help of ex-intelligence agent Edward “Brill” Lyle (Gene Hackman), Dean attempts to throw Reynolds off his trail and prove his innocence.

Minority Report (Spielberg, 2002) Based on a story by famed science fiction writer Philip K. Dick, “Minority Report” is an action-detective thriller set in Washington D.C. in 2054, where police utilize a psychic technology to arrest and convict murderers before they commit their crime. Tom Cruise plays the head of this Precrime unit and is himself accused of the future murder of a man he hasn’t even met.

Dogville (von Trier, 2004) A barren soundstage is stylishly utilized to create a minimalist small-town setting in which a mysterious woman named Grace (Nicole Kidman) hides from the criminals who pursue her. The town is two-faced and offers to harbor Grace as long as she can make it worth their effort, so Grace works hard under the employ of various townspeople to win their favor. Tensions flare, however, and Grace’s status as a helpless outsider provokes vicious contempt and abuse from the citizens of Dogville.

Code 46 (Winterbottom, 2004) In a dystopian future, insurance fraud investigator William Gold (Tim Robbins) arrives in Shanghai to investigate a forgery ring for “papelles,” futuristic passports that record people’s identities and genetics. Gold falls for Maria Gonzalez (Samantha Morton), the woman in charge of the forgeries. After a passionate affair, Gold returns home, having named a coworker as the culprit. But when one of Gonzalez’s customers is found dead, Gold is sent back to Shanghai to complete the investigation.

Caché (Hidden) (Haneke, 2005) A Parisian couple terrorised by anonymous videos which hint at a long-kept secret.

The Lives of Others (Henckel von Donnersmarck, 2006) In 1983 East Berlin, dedicated Stasi officer Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), doubting that a famous playwright (Sebastian Koch) is loyal to the Communist Party, receives approval to spy on the man and his actress-lover Christa-Maria (Martina Gedeck). Wiesler becomes unexpectedly sympathetic to the couple, then faces conflicting loyalties when his superior takes a liking to Christa-Maria and orders Wiesler to get the playwright out of the way.

Disturbia (Caruso, 2007) Ever since his father died, young Kale (Shia LaBeouf) has become increasingly sullen and withdrawn, until he finds himself under house arrest. With cabin fever setting in, he turns his attention to spying on his neighbors, becoming increasingly suspicious that one of them is a serial killer. However, he wonders if he is right, or if his overactive imagination is getting the better of him.

Look (Rifkin, 2007) Interconnected stories are told entirely through images captured on security cameras in storage rooms, police cars, parking lots, shopping malls and other locations. Store manager Tony (Hayes MacArthur) has affairs with the women who work under him, high schooler Sherri (Spencer Redford) schemes to seduce teacher Berry (Jamie McShane), a pedophile stalks his next victim at a mall food court and two thieves go on a killing spree that links to other tales witnessed by the unseen electronic eyes.

We Live in Public (Timoner, 2009) In 1999, Internet entrepreneur Josh Harris recruits dozens of young men and women who agree to live in underground apartments for weeks at a time while their every movement is broadcast online. Soon, Harris and his girlfriend embark on their own subterranean adventure, with cameras streaming live footage of their meals, arguments, bedroom activities and bathroom habits. This documentary explores the role of technology in our lives, as it charts the fragile nature of dot-com economy.

The Social Network (Fincher, 2010) In 2003, Harvard undergrad and computer genius Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) begins work on a new concept that eventually turns into the global social network known as Facebook. Six years later, he is one of the youngest billionaires ever, but Zuckerberg finds that his unprecedented success leads to both personal and legal complications when he ends up on the receiving end of two lawsuits, one involving his former friend (Andrew Garfield).

Erasing David (Bond & McDougall, 2010) Dramatized documentary (docufiction) film from the United Kingdom. Stating that as of today the UK is “one of the three most intrusive surveillance states in the world, after China and Russia”, director and performer David Bond tries to put the system to the test. After anonymously setting up private investigators Cerberus Investigations Limited to trace him, he tries to disappear.

Terms and Conditions May Apply (Hoback, 2013) Filmmaker Cullen Hoback exposes the erosion of online privacy and what information governments and corporations are legally taking from citizens each day.

Citizenfour (Poitras, 2014) After Laura Poitras received encrypted emails from someone with information on the government’s massive covert-surveillance programs, she and reporter Glenn Greenwald flew to Hong Kong to meet the sender, who turned out to be Edward Snowden.

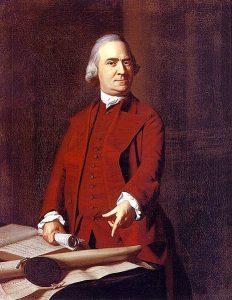

(1750) which portrayed the wealthy couple showing off their wealth. It reminds me of the boastful elements of social media. The next portrait was John Singleton Copley’s

(1750) which portrayed the wealthy couple showing off their wealth. It reminds me of the boastful elements of social media. The next portrait was John Singleton Copley’s