As today is the last week before the Scottish referendum which will decide whether Scotland will become an independent country I could not help but begin the lecture with a shout out to this coming monumental date. I find it hard to believe that the world is talking about anything else.

But the real point of today’s class was to talk about digital divides and net neutrality. To begin this I began by explaining how the Internet became this amazing thing it is today. We tend to take it’s coolness for granted because it is so cool (I recognize that this is circular reasoning but that is the way it is often explained).

One of the unexplained reasons the Internet became cool depends on the business model that is used. In the early days we paid for the time we were connected. This pay-as-you-go model is great but it does have a dampening effect. Since you are constantly paying the impetus is to be quick. Being quick means that the content will be light and fast to be usable.

This business model is the same as the telephone model has been for most of it’s history. We paid per minute and by distance. We were taught to be brief and idle chatting was discouraged. This is also because the infrastructure was originally highly wasteful and could only serve one user per line.

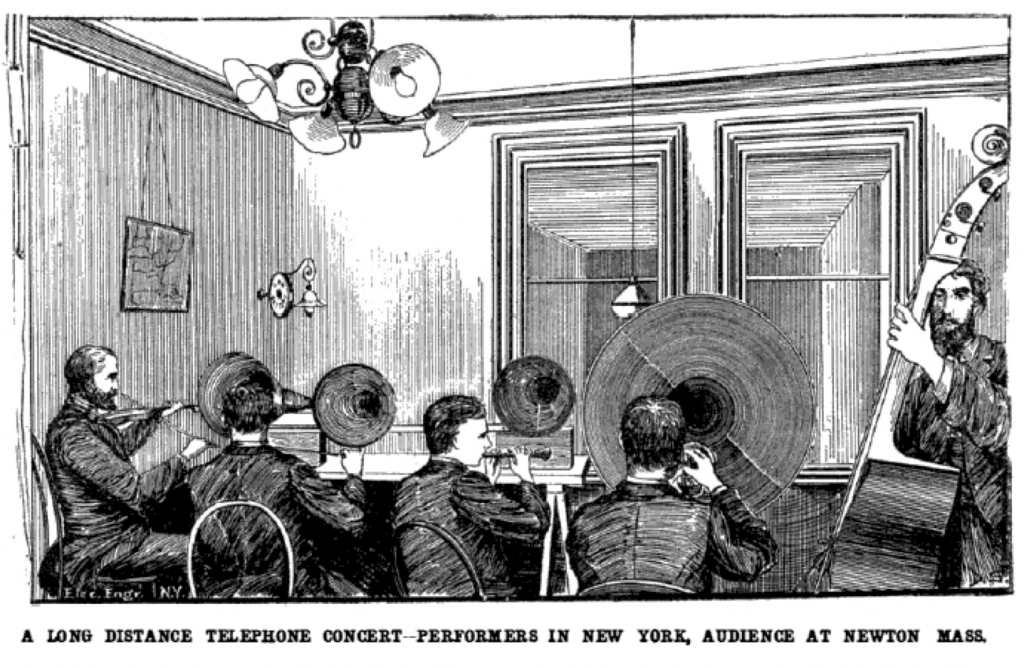

If the telephone had developed into a monthly charge instead, we could have seen a great deal more innovation and use of the system we could have created the Internet much much earlier. This counterfactual is not totally strange. The early ideas for the telephone included such oddities as dial-up concerts. Such as the one reported in Scientific American, (February 28, 1891):

In a lecture recently delivered in the Town Hall at Newton, Mass., Mr. Pickernell described the methods employed in the transmission of music by telephone. His remarks were very forcibly illustrated by the reception in the lecture hall of music transmitted over the long distance lines from the telephone building, at No. 18 Cortlandt Street, New York, and our engraving, made from a photograph taken at the time, shows the arrangement of the performers.

But as we all know this was not the way the telephone evolved. The Internet on the other hand did move in that direction. Rather quickly we moved from dial-up modems to fixed connections. Speed was important – but even more important was the fact that the user never had to worry about the time she was online. Downloading large files, streaming, idle browsing and most all of our online lives stems from the point where we stopped worrying about the cost of access to the Internet.

Another point that needs to be stressed is that we often confuse the Internet, the Web and what we do on our mobile devices. Put very simply the Internet is the cables and servers the infrastructure upon which several applications (such as email, netflix and the Web run upon). What we do on our mobile devices is mostly using apps which run on the Internet (but not necessarily the web).

So while the web which was developed by Tim Berners Lee became huge because he chose to give the system away without trying to patent or close it. It is now shrinking because we are becoming more dependent upon our mobile devices. For the longest time we said “the Internet” when we really meant “the Web” and now we say “the Web” when we really mean “the Internet” (via apps on our devices).

This may seem to be pedantic distinctions but they are important as each of these technologies have different strengths and weaknesses and different affordances and control mechanisms.

Once this was established we looked at this map illustrating:

What you’re looking at is a map of nearly every device that was connected to the internet on August 2. Or, at least, a map of ones that responded to a ping request from John Matherly, an internet cartographer. Motherboard

When we say everybody uses the Internet this is the everybody to which we are referring. The large dark areas are those without this, for us, basic technology. Additionally there are small places with more connectivity than the areas we would normally see as technology dense. The map also raises interesting questions about divisions created by culture and language and the problems of measurement when countries such as China are behind a firewall.

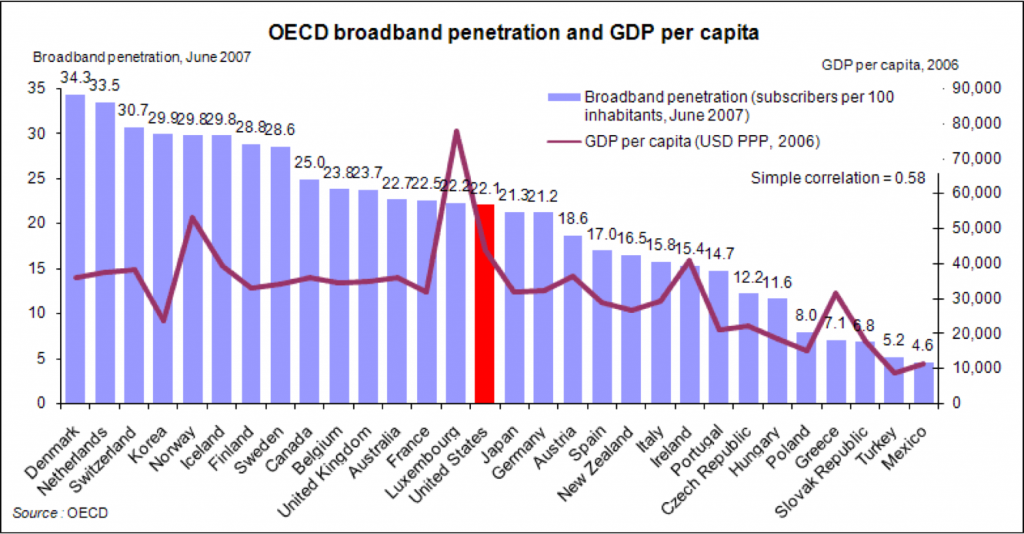

We also looked at an array of charts illustrating OECD statistics on broadband penetration per capita, average monthly subscription price, and average download speeds.

The USA has an average broadband penetration among OECD countries but it also has the highest number of total internet subscribers by far seen in absolute numbers.

The USA has an average broadband penetration among OECD countries but it also has the highest number of total internet subscribers by far seen in absolute numbers.

In order to have some form of consensus for our discussion on the digital divide I put forward this description:

… a gap between those who have ready access to information and communication technology and the skills to make use of those technology and those who do not have the access or skills to use those same technologies within a geographic area, society or community. It is an economic and social inequality between groups of persons.

The factors that are persistently pointed to as being the root causes of the digital divide are

- Cost (technology and connection)

- Know-how (how to connect, how to use devices, what to do when something goes wrong, overcoming cultural divides etc)

- Recognizing the benefit

The latter is very interesting as most users do not need to explain why they benefit but non-users manage to make their lives work without access. It is difficult to demonstrate to non-users that they would benefit from using the technology. Indeed that they would benefit so much that it is worth struggling to overcome the barriers of cost and know-how.

Then we moved the discussion over to the Pew research report African Americans and Technology Use, which showed

African Americans trail whites by seven percentage points when it comes to overall internet use (87% of whites and 80% of blacks are internet users), and by twelve percentage points when it comes to home broadband adoption (74% of whites and 62% of blacks have some sort of broadband connection at home). At the same time, blacks and whites are on more equal footing when it comes to other types of access, especially on mobile platforms.

All things being equal there should be no difference in technology use. And yet there is a gap of seven percentage points. Considering most countries desire to transfer more business and services online this is a worrying number of outsiders. Remember, both groups should have users who don’t see a need for the technology – this gap is not about them.

When it came to smartphone ownership the difference was not significant (53% of whites and 56% of blacks) but I found this interesting taken in conjunction with the earlier numbers. Were some users choosing mobile devices over broadband? What were the consequences of this? Stephanie Chen was interviewed in Salon

“You can’t do your homework on a smartphone; you can’t help your kids with their homework on a smartphone; you can’t write your résumé on a smartphone. You can’t do any of that on a smartphone… As a test, I went through the process and tried to apply for a job at Walmart on a phone. It was an arduous process.”

Once again it is vital to remember that each device has it’s affordances that enable and discourage behavior.

Following this we touched briefly on the concepts of digital natives, digital immigrants and digital tourists. I can only refer back to an earlier rant of mine on the subject:

During the discussions one of the topics that came up was the digital divide which is claimed to exist between young and old (whatever do these epitaphs mean?) and then it was only natural to bring up the horrible term digital natives, digital immigrants and digital turists. All these terms were popularized by Marc Prensky and are completely horrific. And of course very popular. There were voices of reason among the crowd but at the same time the catchy phrase seemed to win over intelligent discussion.

There are several problems with the metaphor, not to mention the built in racism. In most languages, calling someone a native smacks of arrogance, a touch of racism and good old fashioned colonialism.

Who is the native? So who is the native and how does one become one? Obviously the idea here is that the youth of today are all tech-savvy and understand technology while the older generation is good at saying stuff like “I remember when…” and handling analog technology. Seriously what a load of dog doodoo. The fact that we lack common areas of interest is not a digital divide. Young people tend to have different tastes in music, love, hobbies, work, films, books than older people. Even Beethoven’s father probably complained at his sons taste in music.

Are they a group? The young are not a homogeneous group, but then again the question could be put forward if homogeneous groups actually exist at all? Does the Englishman really exist? What is it the natives are supposed to understand? This is the biggest problem with the metaphor. Yes, there are hoards of young folk who can easily send hundreds of text messages per day but does that identify them as digital? Does this mean that they are fundamentally different from those who can hardly use the mobile telephones?

The problem is that the idea of the digital native seems to be that they are (1) comfortable using all digital technology and, (2) understand all digital technology. This is most obviously wrong. The ability to be on Facebook does not prepare you for editing wikipedia, blogging or twitter. The ability to use wikipedia has nothing to do with being popular on twitter. And none of these abilities have anything to do with the ability to use the most of the functions in the simplest word processors.

The understanding of technology, how it works, what it means – in addition to its social, economic and cultural impact is quite often totally lost on these so-called natives. I mean no disrespect (even though saying this usually makes things worse) but being an enthusiastic user has no relation to understanding technology.

Metaphors are supposed to exist to help us understand complex ideas. When they do not fulfill this basic purpose they are useless or worse harmful to our understanding. A misguided metaphor is worse than no metaphor at all. And the concept of digital natives does not aid understanding – it only creates barriers.

It was then time to deal with net neutrality and in order to do this in a more entertaining manner I showed a part of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver: Net Neutrality (HBO)

And finally closed by appealing to them to go and read up on net neutrality, and in particular, check out the website Battle for the Net since there is still time for those who feel it to be important to react and to show politicians that the open net is something ordinary people are passionate about.

Here are the slides I used for this presentation: