For a large period of time in computing history software was not seen as the primary component. It was all about the hardware, the machine. The code that made the machine work and useable was simply seen as part and parcel of the machine.

One reason for this may be the way in which we tended to understand software. Another reason may have been that hardware of that size and complexity was not sold, it was leased. The “buyer” therefore was paying for a solution rather than a system. This was a very lucrative way of doing business.

The early punch card system that became the solution for the US Census was the Hollerith Tabulating Machine, these were leased to the Census Bureau. Hollerith’s company would later merge with others to become IBM whose punch card tabulators were leased to governments and organizations around the world. One advantage of the leasing system is that the company could control which cards were used in the system and also charge for maintenance and training.

With digitalisation many companies made source code available and engineers could make changes to the software. Improvements could be included into the code and sold on to the next company.

In 1969, IBM began to charge separately for (mainframe) software and services, and ceased to supply source code. By withholding the source code, only the company could make changes (and presumably charge their buyers for these changes).

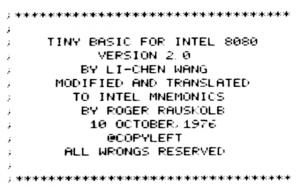

The ability to “own” software, or at least control it through copyright was beginning to become a discussion among programmers. For example in 1976 Dr Li-Chen Wang released Tiny Basic under a Copyleft license which included the catch phrase “All Wrongs Reserved”  It is fair to say that the history of free software (and copyleft) truly begins with Richard Stallman‘s attempts to create a “technical means to a social end.” The story behind the creation of free software starts with his attempts to make a printer work and the company’s (who owned the printer) refusal to give access to the necessary code. He launched the GNU Project in 1983.

It is fair to say that the history of free software (and copyleft) truly begins with Richard Stallman‘s attempts to create a “technical means to a social end.” The story behind the creation of free software starts with his attempts to make a printer work and the company’s (who owned the printer) refusal to give access to the necessary code. He launched the GNU Project in 1983.

Free software is all about ensuring that we have access to, and control over, the basic infrastructures of our lives. It is not about having software at no cost – it’s about ensuring that our technology works in ways that suit our lives. In order to enact this the software that is produced by teams and individuals around the world is licensed under the GPL (General Public License) summing up the license is a bit tricky but it is common to refer to the Four Freedoms, to be considered to be Free Software it must:

The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose (freedom 0).

The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1).

Access to the source code is a precondition for this. The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor (freedom 2).

The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3).

A precondition for these freedoms is that the code must be accessible to those who would want to read it. The importance of Free Software is much like the arguments for free speech or freedom of information. It is not that everyone wants, or has the competency, to use these rights but without them all of us are a little less informed about what is happening around us.

Once again it is important to stress Free Software is not about price. Nor is it about doing whatever you like with the code. From the Free Software Manifesto (1985)

GNU is not in the public domain. Everyone will be permitted to modify and redistribute GNU, but no distributor will be allowed to restrict its further redistribution. That is to say, proprietary modifications will not be allowed. I want to make sure that all versions of GNU remain free.

It is a gift with a very clear condition.

Free Software is sometimes confused with Open Source software. They are both similar but they have different conditions:

The term “open source” software is used by some people to mean more or less the same category as free software. It is not exactly the same class of software: they accept some licences that we consider too restrictive…

A common difference that can easily be seen in many open source licenses is the lack of the clear condition that nothing can be made into proprietary software.

Here are the slides I used.