The presentation yesterday dealt with moving regulation from the physical world to the digital environment. My goal was to show the ways in which regulation occurs and in particular to go beyond the simplistic “wild west” ideology online – at the same time I wanted to demonstrate that online behavior is controlled by more elements than the technological boundaries.

In order to do this, I wanted to begin by demonstrating that the we have used tools for a long period of time and that these tools enable and support varying elements of control. And since I was going to take a historic approach I could not resist taking the scenic route.

In the beginning was the Abacus. Developed around 2400 BCE in Mesapotamia this amazing tool for extending the power of the brain to calculate large numbers (which is basically what your smartphone does but much much more…). The fascinating thing with the abacus is that despite the wide range of digital devices it remains in use today (but it is in deep decline).

The decline of the Chinese abacus the Suanpan

Suanpan arithmetic was still being taught in school in Hong Kong as recently as the late 1960s, and in Republic of China into the 1990s. However, when hand held calculators became readily available, school children’s willingness to learn the use of the suanpan decreased dramatically. In the early days of hand held calculators, news of suanpan operators beating electronic calculators in arithmetic competitions in both speed and accuracy often appeared in the media. Early electronic calculators could only handle 8 to 10 significant digits, whereas suanpans can be built to virtually limitless precision. But when the functionality of calculators improved beyond simple arithmetic operations, most people realized that the suanpan could never compute higher functions – such as those in trigonometry – faster than a calculator. Nowadays, as calculators have become more affordable, suanpans are not commonly used in Hong Kong or Taiwan, but many parents still send their children to private tutors or school- and government- sponsored after school activities to learn bead arithmetic as a learning aid and a stepping stone to faster and more accurate mental arithmetic, or as a matter of cultural preservation. Speed competitions are still held. Suanpans are still being used elsewhere in China and in Japan, as well as in some few places in Canada and the United States.

Continuing on the story of ancient technology pointed to the Antikythera Mechanism an analogue computer from 100BCE designed to predict astronomical positions and eclipses. The knowledge behind this machinery would be lost for centuries.

In the 17th century Wilhelm Schickard & Blaise Pascal developed mechanical addition and subtraction machines but the more durable development was that of the slide rule

The Reverend William Oughtred and others developed the slide rule in the 17th century based on the emerging work on logarithms by John Napier. Before the advent of the pocket calculator, it was the most commonly used calculation tool in science and engineering. The use of slide rules continued to grow through the 1950s and 1960s even as digital computing devices were being gradually introduced; but around 1974 the electronic scientific calculator made it largely obsolete and most suppliers left the business.

Despite its almost 3 centuries of dominance few of us today even remember the slide rule, let along know how to use one.

While the analogue calculating devices were both useful and durable most of the machines were less so. This is because they were built with a fixed purpose in mind. The early addition and subtraction machines were simply that. Addition and subtraction machines. They could not be used for other tasks without needing to be completely rebuilt.

The first examples of programmable machinery came with the Jacquard loom first demonstrated in 1801. Using a system of punch cards the loom could be programmed to weave patterns. If the pattern needed to be changed then the program was altered. The punch cards were external memory systems which were fed into the machine. The machine did not need to be re-built for changes to occur.

The looms inspired both Charles Babbage and Herman Hollerith to use punch cards as a method for imputing data in their calculating machines. Babbage is naturally the next famous point in our history. His conceptual Difference Engine and Analytical Engine have made him famous as the father of the programmable computer.

But as his devices remained to the largest part theoretical constructs I believe that the more important person of this era is Ada Lovelace who not only saw the potential in these machines but, arguably, saw an even greater potential than Babbage himself envisioned. She was the first computer programmer and a gifted mathematician.

Few scientists understood Babbage’s breakthrough, but Ada wrote explanations of the Analytical Engine’s function, its advantage over the Difference Engine, and included a method for using the machine in calculating a sequence of Bernoulli numbers.

The next step in this story Hollerith’s tabulating machine. While the level of computing is not a major step the interesting part is the way it came to be and the solutions that were created. The American census of 1880 took 8 years to conduct and it was predicted that the 1890 census would take 13 years to conduct. This was unacceptable and the census bureau looked for technical solutions. Hollerith built machines under contract for the Census Office, which used them to tabulate the 1890 census in only one year.

Hollerith’s business model was ingenious. He did not sell the machines, he sold his services. The governments and corporations around the world that came to rely on his company had no control but had to pay the price for his technical expertise. Hollerith’s company eventually became the core of IBM.

The point being that Hollerith positioned his company as holding the key role between the user and the data.

The progress in machinery and thoughts around machinery moved forward at a steady pace. Then making rapid progress during the second world war with names like Bletchley Park, the Colossus (the world’s first programmable digital electronic computer) and Alan Turing.

While most people could hardly comprehend the power of a computer, Vannevar Bush wrote his famous article on the Memex As We May Think in 1945. Here were visions of total information digitization and retrieval. Ideas that are now possible after half a century of modern computing history.

And with this we leap into the modern era, first with the Internet, then personal computers, and the advent of the world wide web.

The fascinating thing here is the business model becomes more clearly what Hollerith envisioned it. It was about becoming the interface between the user and the data. This is where the power lay.

When IBM was at it’s height Bill Gates persuaded them to begin using his operating system. He also persuaded them to allow him not to be exclusive to them. The world realized that it wasn’t the hardware that was important – it was what we could do with it that counted. Other manufacturers came in and IBM lost its hold of the computer industry.

When Tim Berners Lee developed the web and the first web browser and released them both freely online he created a system which everyone could use without needing licenses or payment. The web began to grow at an incredible rate.

Windows was late in the game. They still believed in the operating system but the interface between the user and the data was shifting. No matter which operating system or hardware you used it was all about accessing data online.

With Windows95 Microsoft took up the fight for the online world against the then biggest competitor Netscape. Microsoft embedded their browser Internet Explorer in the operating system and made it increasingly difficult for users to remove it. This was the beginning of the browser wars, a fight for control of the interface between the user and the data.

The wars eventually lost their relevance with the development of a new type of company offering a new version of a search engine. When Google came on the scene it had to compete with other search engines but after a relatively quick battle it became the go-to place where Internet users began their online experiences. It had become the interface between the users and the data. It didn’t matter which hardware, software, or browser you used… everyone began with Google.

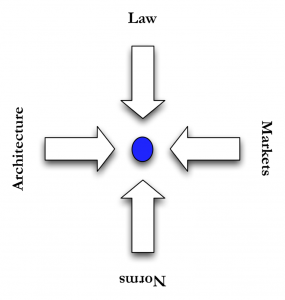

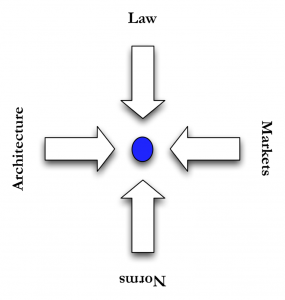

At this point I introduced the four modalities of regulation used by Lawrence Lessig and presented in his work The Code from 1999.

Contrary to what many believe, regulation takes many forms. We regulate with social norms, with market solutions and with architecture (as well as laws). Naturally none of these modalities occur in isolation but we often tend to forget that much of our regulation is embedded in social, economic and physical contexts. If any of these contexts change then the law must adapt to encompass this change.

Contrary to what many believe, regulation takes many forms. We regulate with social norms, with market solutions and with architecture (as well as laws). Naturally none of these modalities occur in isolation but we often tend to forget that much of our regulation is embedded in social, economic and physical contexts. If any of these contexts change then the law must adapt to encompass this change.

Using the offline problem of slowing down traffic I pointed to the law which hangs out speed signs, the market regulation of the price of a speeding ticket and the time it takes to negotiate its payment. Social attempts to slow traffic occur when people in the neighborhood hang signs warning drivers of children in the area. They are appealing to the drivers better nature.

And the architecture of the road. If we want to slow down cars it is much more efficient to change the road than to hang up a sign. Make it curvy, make it bumpy, change its colors there are an array of things that can be done to limit or slow access. The problem with using technology (or architecture) is that it is absolute. If we put speed bumps in the road then not even someone driving with good cause can speed. Even someone attempting to drive a heart attack victim to the hospital must slow down.

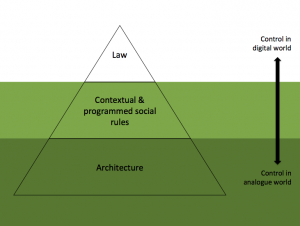

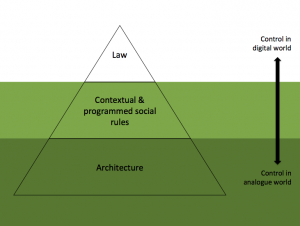

The more we move from the analogue into the digital world the less control that is afforded through the law and the more ability we have to change the realities in which we live. Architecture or technology is more pliable as a form of regulation.

The more we move from the analogue into the digital world the less control that is afforded through the law and the more ability we have to change the realities in which we live. Architecture or technology is more pliable as a form of regulation.

In closing I asked the class to list regulatory examples which occur when attempting to access information online via their smartphones. The complex interface between them and the data included new levels like the apps they use, the apps that their phones allow, their payment plans, social control online, social control offline and a whole host of other regulatory elements.

And here are the slides I used:

(1750) which portrayed the wealthy couple showing off their wealth. It reminds me of the boastful elements of social media. The next portrait was John Singleton Copley’s

(1750) which portrayed the wealthy couple showing off their wealth. It reminds me of the boastful elements of social media. The next portrait was John Singleton Copley’s